Contributor: Assoc Prof G.V. Shivashankar, MBI, Singapore Updated on: August 2012

Contribute | Nuclear MechanotransductionEukaryotic cells constantly sense their local microenvironment through surface mechanosensors for physical and soluble signals. Integration of these physicochemical cues by cells not only results in cytoskeletal modifications but also significantly impinges on the functional nuclear landscape and its mechanical properties. However, its physical properties such as morphology, position, stiffness and organization ought to be maintained for proper functioning of the cell. In this topic, we describe the various steps involved in transmission of environmental cues to the nucleus, how they affect the nuclear architecture and function leading to changes that elicit a response. We also discuss the interdependence of the cytoskeletal and nuclear mechanics in the process of adaptation to the constantly changing environment in order to maintain homeostasis at the cellular as well as systems level. Contents:Unit 1: Nuclear PrestressUnit 2: Higher order chromatin organization and transcription Unit 3: Nuclear mechanosignaling pathways Unit 4: Nuclear mechanics in differentiation and diseases Unit 5: Modeling nuclear mechanics: active stresses, polymers and signaling ————————————–

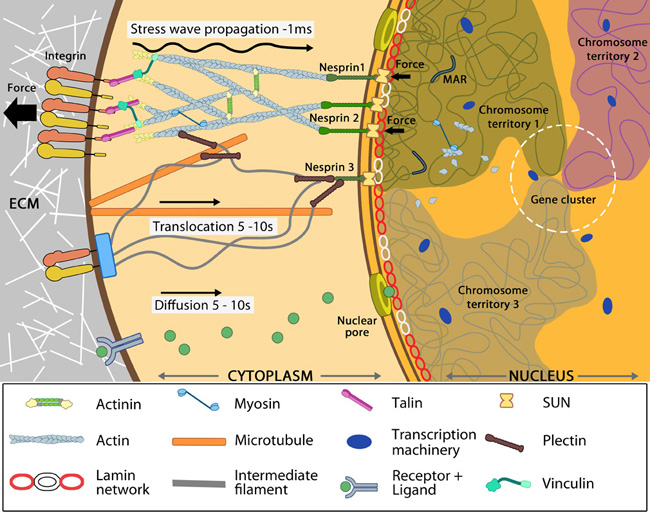

An overviewAs an integral part of cellular behavior, cells are sensitive to matrix rigidity, local geometry and stress or strain applied by external factors [1]. In recent years, it has been established that an extensive network of protein assembly couples the cytoskeleton to the nucleus [2] (reviewed in [3]) and that condensation forces of the chromatin balance cytoskeletal forces resulting in a prestressed nuclear organization [4, 5]. Thence, besides remodeling cytoskeletal filaments, the forces generated within the cell and that experienced at distant cell surface sites converge to the nucleus. This can happen either by physical transmission along the linked cytoskeleton [6] (reviewed in [3]) or by chemical signaling, where transcription regulators get transported to the nucleus upon activation [7, 8] (reviewed in [9]). These mechanosignals have a significant impact on the mechanical properties of the nucleus such as shape and rigidity (reviewed in [6, 10]) through modification of the scaffolding proteins at the nuclear envelope and interior.Figure: Nuclear connectivity and mechanotransduction. Force experienced by integrins at the cell surface via mechanosensing structures like focal adhesions (integrin cluster linked to actin network), hemidesmosomes (blue rectangle) or cell-cell contact (not shown) is accumulated, channeled through SUN1/SUN2 form the LINC (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton) complexes connecting further to the nuclear lamina (red and white lamin network) and hence the attached nuclear scaffold proteins (actin and myosin). Chromatin attaches directly to the lamina and to other scaffolding proteins through the matrix attachment regions (MARs). Upon sensing the force, the nuclear scaffold help repositioning the chromatin thus affecting nuclear prestress and activating genes within milliseconds. Spatial segregation of chromosomes with defined territories is represented as colored compartments inside the nucleus. The dotted circle highlights looping of genes from different chromosomes to form a cluster in 3D space and share transcription apparatus (navy ovals). On the contrary, chemical signaling mediated by motor-based translocation along cytoskeletal filaments or diffusion of activated regulatory factors takes few seconds. Adapted from [6, 9]. The mechanical cues are sorted in a highly regulated manner leading to chemical modification of the DNA, nucleoskeletal proteins and histones [11]. The process encompasses reorganization of chromosomes and spatiotemporal assembly of dynamic transcription compartments at specific promoters, which often cluster at interchromosome territories in the 3D nuclear space and share transcription machinery [12, 13] (reviewed in [9, 14]). Thus combinatorial control of genes is achieved depending on the cellular context and nature of the external signal (reviewed in [15]). Therefore akin to the cytoskeleton, nucleus has also been demonstrated to act as a load bearing organelle that physically transmits mechanical cues [16] leading to altered gene expression patterns (reviewed in [17, 18]) and hence a plethora of cellular traits such as shape, motility, differentiation and development [19, 20, 21](reviewed in [22]). What properties of the nucleus make it a substrate for mechanotransduction?Similar to the concept of long distance force propagation along cytoskeleton based on the tensegrity model, the prestressed nuclear state due to intracellular force balance enables mechanotransduction [4, 23]. Both the nuclear envelope and nuclear interior contribute to its mechanical properties.Several studies on nuclear mechanical properties have convincingly established that the nucleus is about 3-10 times stiffer than the surrounding cytoplasm depending on cell type [24, 25]. Nuclear stiffness is mainly attributed to lamins A and C, that form a network underneath the nuclear envelope termed ‘nuclear lamina’ [26, 27]. Their role is very evident in the case of stem cells, where lamin A is absent. Hence their nuclei are highly fragile while upon differentiation (expression of lamin A) they stiffen and resist deformation [28]. Further, the plasticity of stem cell nucleus is attributed to enhanced collisions between chromosome interfaces due to lack of spatial organization. Differentiated cells reveal precise cell-type specific positional coordinates for each chromosome through physical anchoring to other chromosomes or scaffolding proteins [29, 30, 31, 32]. Such well-defined interfaces are brought about by the orderly assembly of nuclear structural proteins upon activation of gene expression programs [33, 34]. Microrheology studies have also demonstrated a higher viscoelastic modulus for the nucleoplasm relative to cytoplasm arising primarily due to the heterogeneous chromatin organization [35, 36, 37]. The nuclear envelope behaves like an elastic sac with gel-like viscous contents [38, 39]. Hence it can undergo reversible stiffening or softening and deformation depending on the nature and timescale of force experienced [39, 40, 41]. The importance of nuclear mechanics is reflected in many disease conditions as discussed here. |

References

- Vogel V. & Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006; 7(4):265-75. [PMID: 16607289]

- Maniotis AJ., Chen CS. & Ingber DE. Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997; 94(3):849-54. [PMID: 9023345]

- Stewart CL., Roux KJ. & Burke B. Blurring the boundary: the nuclear envelope extends its reach. Science 2007; 318(5855):1408-12. [PMID: 18048680]

- Mazumder A., Roopa T., Basu A., Mahadevan L. & Shivashankar GV. Dynamics of chromatin decondensation reveals the structural integrity of a mechanically prestressed nucleus. Biophys. J. 2008; 95(6):3028-35. [PMID: 18556763]

- Mazumder A. & Shivashankar GV. Emergence of a prestressed eukaryotic nucleus during cellular differentiation and development. J R Soc Interface 2010; 7 Suppl 3:S321-30. [PMID: 20356876]

- Wang N., Tytell JD. & Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009; 10(1):75-82. [PMID: 19197334]

- Xu J., Zutter MM., Santoro SA. & Clark RA. A three-dimensional collagen lattice activates NF-kappaB in human fibroblasts: role in integrin alpha2 gene expression and tissue remodeling. J. Cell Biol. 1998; 140(3):709-19. [PMID: 9456329]

- Vartiainen MK., Guettler S., Larijani B. & Treisman R. Nuclear actin regulates dynamic subcellular localization and activity of the SRF cofactor MAL. Science 2007; 316(5832):1749-52. [PMID: 17588931]

- Shivashankar GV. Mechanosignaling to the cell nucleus and gene regulation. Annu Rev Biophys 2011; 40:361-78. [PMID: 21391812]

- Dahl KN., Ribeiro AJ. & Lammerding J. Nuclear shape, mechanics, and mechanotransduction. Circ. Res. 2008; 102(11):1307-18. [PMID: 18535268]

- Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature 2007; 447(7143):407-12. [PMID: 17522673]

- Xu M. & Cook PR. Similar active genes cluster in specialized transcription factories. J. Cell Biol. 2008; 181(4):615-23. [PMID: 18490511]

- Schoenfelder S., Sexton T., Chakalova L., Cope NF., Horton A., Andrews S., Kurukuti S., Mitchell JA., Umlauf D., Dimitrova DS., Eskiw CH., Luo Y., Wei CL., Ruan Y., Bieker JJ. & Fraser P. Preferential associations between co-regulated genes reveal a transcriptional interactome in erythroid cells. Nat. Genet. 2010; 42(1):53-61. [PMID: 20010836]

- Misteli T. Beyond the sequence: cellular organization of genome function. Cell 2007; 128(4):787-800. [PMID: 17320514]

- Sutherland H. & Bickmore WA. Transcription factories: gene expression in unions? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009; 10(7):457-66. [PMID: 19506577]

- Hu S., Chen J., Butler JP. & Wang N. Prestress mediates force propagation into the nucleus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005; 329(2):423-8. [PMID: 15737604]

- Chiquet M., Gelman L., Lutz R. & Maier S. From mechanotransduction to extracellular matrix gene expression in fibroblasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009; 1793(5):911-20. [PMID: 19339214]

- Wang JH., Thampatty BP., Lin JS. & Im HJ. Mechanoregulation of gene expression in fibroblasts. Gene 2007; 391(1-2):1-15. [PMID: 17331678]

- Misteli T. & Soutoglou E. The emerging role of nuclear architecture in DNA repair and genome maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009; 10(4):243-54. [PMID: 19277046]

- Mammoto A., Connor KM., Mammoto T., Yung CW., Huh D., Aderman CM., Mostoslavsky G., Smith LE. & Ingber DE. A mechanosensitive transcriptional mechanism that controls angiogenesis. Nature 2009; 457(7233):1103-8. [PMID: 19242469]

- Kumar A. & Shivashankar GV. Mechanical force alters morphogenetic movements and segmental gene expression patterns during Drosophila embryogenesis. PLoS ONE 2012; 7(3):e33089. [PMID: 22470437]

- Dahl KN., Booth-Gauthier EA. & Ladoux B. In the middle of it all: mutual mechanical regulation between the nucleus and the cytoskeleton. J Biomech 2010; 43(1):2-8. [PMID: 19804886]

- Ingber DE. Tensegrity-based mechanosensing from macro to micro. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol.; 97(2-3):163-79. [PMID: 18406455]

- Caille N., Thoumine O., Tardy Y. & Meister JJ. Contribution of the nucleus to the mechanical properties of endothelial cells. J Biomech 2002; 35(2):177-87. [PMID: 11784536]

- Guilak F. Compression-induced changes in the shape and volume of the chondrocyte nucleus. J Biomech 1995; 28(12):1529-41. [PMID: 8666592]

- Lammerding J., Fong LG., Ji JY., Reue K., Stewart CL., Young SG. & Lee RT. Lamins A and C but not lamin B1 regulate nuclear mechanics. J. Biol. Chem. 2006; 281(35):25768-80. [PMID: 16825190]

- Schäpe J., Prausse S., Radmacher M. & Stick R. Influence of lamin A on the mechanical properties of amphibian oocyte nuclei measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2009; 96(10):4319-25. [PMID: 19450502]

- Pajerowski JD., Dahl KN., Zhong FL., Sammak PJ. & Discher DE. Physical plasticity of the nucleus in stem cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007; 104(40):15619-24. [PMID: 17893336]

- Nagele RG., Freeman T., McMorrow L., Thomson Z., Kitson-Wind K. & Lee H. Chromosomes exhibit preferential positioning in nuclei of quiescent human cells. J. Cell. Sci. 1999; 112 ( Pt 4):525-35. [PMID: 9914164]

- Parada LA., McQueen PG. & Misteli T. Tissue-specific spatial organization of genomes. Genome Biol. 2004; 5(7):R44. [PMID: 15239829]

- Bolzer A., Kreth G., Solovei I., Koehler D., Saracoglu K., Fauth C., Müller S., Eils R., Cremer C., Speicher MR. & Cremer T. Three-dimensional maps of all chromosomes in human male fibroblast nuclei and prometaphase rosettes. PLoS Biol. 2005; 3(5):e157. [PMID: 15839726]

- Müller I., Boyle S., Singer RH., Bickmore WA. & Chubb JR. Stable morphology, but dynamic internal reorganisation, of interphase human chromosomes in living cells. PLoS ONE 2010; 5(7):e11560. [PMID: 20644634]

- Meaburn KJ. & Misteli T. Cell biology: chromosome territories. Nature 2007; 445(7126):379-781. [PMID: 17251970]

- Rajapakse I., Perlman MD., Scalzo D., Kooperberg C., Groudine M. & Kosak ST. The emergence of lineage-specific chromosomal topologies from coordinate gene regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009; 106(16):6679-84. [PMID: 19276122]

- Guilak F., Tedrow JR. & Burgkart R. Viscoelastic properties of the cell nucleus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000; 269(3):781-6. [PMID: 10720492]

- Tseng Y., Lee JS., Kole TP., Jiang I. & Wirtz D. Micro-organization and visco-elasticity of the interphase nucleus revealed by particle nanotracking. J. Cell. Sci. 2004; 117(Pt 10):2159-67. [PMID: 15090601]

- de Vries AH., Krenn BE., van Driel R., Subramaniam V. & Kanger JS. Direct observation of nanomechanical properties of chromatin in living cells. Nano Lett. 2007; 7(5):1424-7. [PMID: 17451276]

- Rowat AC., Foster LJ., Nielsen MM., Weiss M. & Ipsen JH. Characterization of the elastic properties of the nuclear envelope. J R Soc Interface 2005; 2(2):63-9. [PMID: 16849165]

- Dahl KN., Engler AJ., Pajerowski JD. & Discher DE. Power-law rheology of isolated nuclei with deformation mapping of nuclear substructures. Biophys. J. 2005; 89(4):2855-64. [PMID: 16055543]

- Deguchi S., Maeda K., Ohashi T. & Sato M. Flow-induced hardening of endothelial nucleus as an intracellular stress-bearing organelle. J Biomech 2005; 38(9):1751-9. [PMID: 16005465]

- Philip JT. & Dahl KN. Nuclear mechanotransduction: response of the lamina to extracellular stress with implications in aging. J Biomech 2008; 41(15):3164-70. [PMID: 18945430]