Contents

1.1 Role of Mechanobiology in Shaping Cells and Tissues 1.2 Common Themes In Mechanobiology 1.3 Types of Mechanosensing 1.4 Types of Forces Cells Encounter 1.5 The Dynamic Cytoskeleton 1.6 Common Features of Polymeric Cytoskeletal Systems 1.7 How Does the Cytoskeleton Transmit Mechanical Forces? Contribute

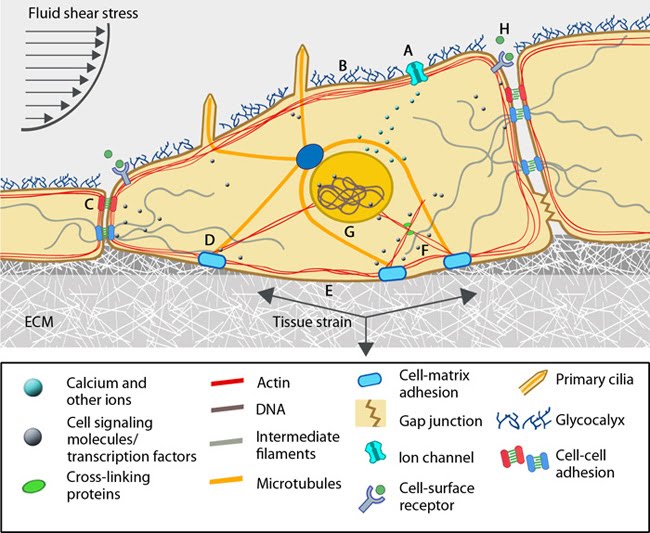

| Essential Info: What is Mechanobiology?

|

References

- Vogel V. Mechanotransduction involving multimodular proteins: converting force into biochemical signals. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 2006; 35:459-88. [PMID: 16689645]

- Vogel V. & Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006; 7(4):265-75. [PMID: 16607289]

- Ingber DE. Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1997; 59:575-99. [PMID: 9074778]

- Geiger B., Bershadsky A., Pankov R. & Yamada KM. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix–cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001; 2(11):793-805. [PMID: 11715046]

- Choquet D., Felsenfeld DP. & Sheetz MP. Extracellular matrix rigidity causes strengthening of integrin-cytoskeleton linkages. Cell 1997; 88(1):39-48. [PMID: 9019403]

- Riveline D., Zamir E., Balaban NQ., Schwarz US., Ishizaki T., Narumiya S., Kam Z., Geiger B. & Bershadsky AD. Focal contacts as mechanosensors: externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mDia1-dependent and ROCK-independent mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 2001; 153(6):1175-86. [PMID: 11402062]

- Shivashankar GV. Mechanosignaling to the cell nucleus and gene regulation. Annu Rev Biophys 2011; 40:361-78. [PMID: 21391812]

- Geiger B., Spatz JP. & Bershadsky AD. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009; 10(1):21-33. [PMID: 19197329]

- Jaalouk DE. & Lammerding J. Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009; 10(1):63-73. [PMID: 19197333]