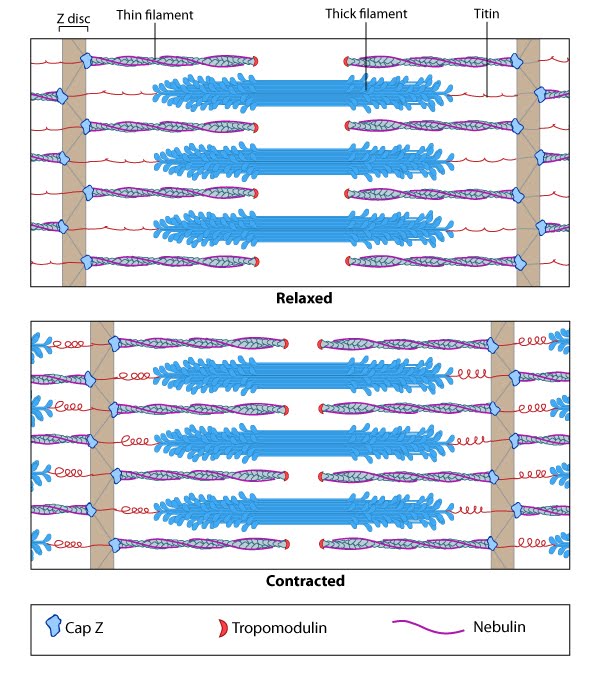

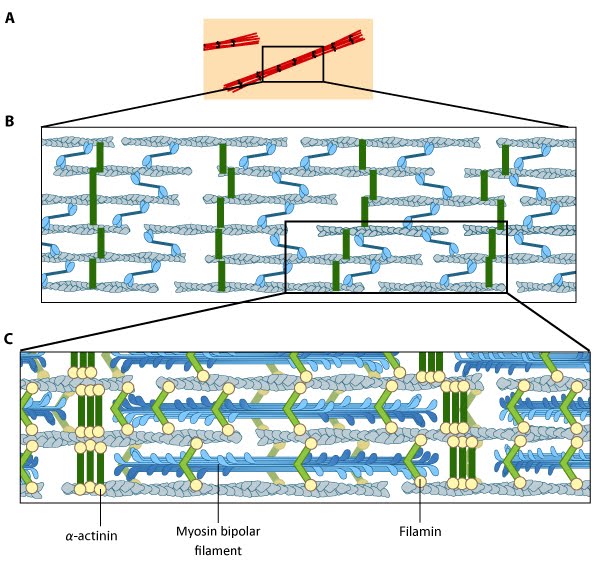

Motor Proteins in Mechanobiology4.3 An Example of Function: A Role in ContractionAs described in the previous chapter, numerous motor proteins exist and each possess unique characteristics that allow them to facilitate different processes and functions. Even within the myosin superfamily variation exists in structure and function of each member.One example of a process in which the motor proteins are involved is in the formation and function of contractile bundles. Contractile Bundles in Skeletal MuscleIn skeletal muscle cells, myosin II forms only thick filaments and they are arranged within a scaffold of actin thin filaments (along with numerous other proteins) into higher order fibrous structures known as sarcomeres. Each sarcomere contains numerous repeating units of interlinked thick and thin filaments, and the opposite orientation of the myosin heads causes adjacent actin filaments to slide past each other during muscle contraction. Each sarcomere is ~2 µm long in resting muscle, but this length is shortened by as much as 70% after muscle contraction. Muscle contraction is regulated by calcium levels [1] and by the troponin regulatory system (see figure “Tropomyosin stabilizes thin filaments“). Although actin subunits continue to turn-over at both ends of the thin filament, this exchange is relatively slow, making the actin filaments in sarcomeres relatively more stable when compared to the actin filaments found in other cell types.Video: Sliding filament theory of muscle contraction. [Video was uploaded to YouTube by avice01 and created by Sara Egner using electron micrography from P M Motta, P M Andrews, K R Porter and J Vial.] Figure: Actin-myosin contraction in muscle cells. The plus end of thin filaments are protected by CapZ capping protein and the minus ends are bound by tropomodulin. The thin filaments are stabilized along the groove of the helix by nebulin, which is also thought to regulate the length of the filament. Both the thin filaments and the bipolar thick filaments are attached to the sarcomere at a region known as the Z disc, which is built from CapZ and α-actinin (not shown). During muscle contraction, the myosin heads of the thick filament walk towards the plus end of the thin filaments (towards the Z disc); because the thin filaments are oriented in opposite directions, myosin movement causes the entire sarcomere length to shorten. The thick filaments are attached to the Z disc by the flexible protein, titin, which acts as a molecular ‘spring’.Force-induced folding/unfolding of titin helps keep the thick filaments positioned in the middle of the sarcomere and it helps the sarcomere to recover its original state after contraction. Contractile Bundles in Nonmuscle CellsIn nonmuscle cells, myosin II associates with actin filaments to form contractile structures known as stress fibers along the lower surfaces where the cell is anchored to its substrate. In epithelial cells, contractile bundles are also prominent in the adhesion belt (aka adherens belt; see also “adherens junction“), which helps to maintain the stability and integrity of epithelial cell sheets. The contractile bundles in nonmuscle cells are similar to skeletal muscle fibers, but they are smaller (~0.4 µm in fibroblasts), less organized, and they contain different accessory proteins [2]. Historically speaking, the mechanism of actomyosin contraction for nonmuscle actin was examined using amoebae proteins Dictyostelium, Acanthamoeba) because the actin is very similar to muscle actin [3]; these initial studies showed the rate of ATP hydrolysis by myosin (and hence myosin movement) varies directly with the actin concentration [4]. Further studies using isolated stress fibers from fibroblasts confirmed that stress fibers are contractile and shorten by as much as 25% [5]. Myosin II bundle formation and contractile activity in nonmuscle cells is regulated by phosphorylation [6].Figure: Stress fiber structure. This schematic representation of a stress fiber was constructed based on evidence obtained using electron microscopy [2, 5]. (A) Isolated stress fibers have a banded appearance, with bundles of actin filaments interspersed with semiperiodic electron-dense regions. (B) The electron-dense regions are rich in actin crosslinking proteins, namely α-actinin. Bipolar myosin II filaments lie between the loosely packed actin filaments in the regions that lack α-actinin (for simplicity, the myosin filament is shown as a single bipolar molecule). (C) A high resolution view of the bipolar myosin filament heads interspersed between the regions high in α-actinin content. Relative to α-actinin, the more flexible actin crosslinking protein, filamin, is dispersed throughout the stress fiber. |

References

- Luchi RJ. & Kritcher EM. Drug effects on cardiac myosin adenosine triphosphatase activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1967; 158(3):540-5. [PMID: 4294509]

- Langanger G., Moeremans M., Daneels G., Sobieszek A., De Brabander M. & De Mey J. The molecular organization of myosin in stress fibers of cultured cells. J. Cell Biol. 1986; 102(1):200-9. [PMID: 3510218]

- Woolley DE. An actin-like protein from amoebae of dictyostelium discoideum. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1972; 150(2):519-30. [PMID: 4261413]

- Spudich JA. Biochemical and structural studies of actomyosin-like proteins from non-muscle cells. II. Purification, properties, and membrane association of actin from amoebae of Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biol. Chem. 1974; 249(18):6013-20. [PMID: 4278010]

- Kreis TE. & Birchmeier W. Stress fiber sarcomeres of fibroblasts are contractile. Cell 1980; 22(2 Pt 2):555-61. [PMID: 6893813]

- Katoh K., Kano Y., Masuda M., Onishi H. & Fujiwara K. Isolation and contraction of the stress fiber. Mol. Biol. Cell 1998; 9(7):1919-38. [PMID: 9658180]