Integrin extension[Edit]

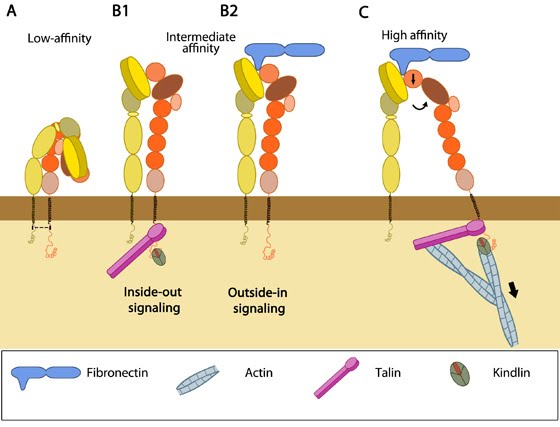

Upon alteration in the transmembrane and their proximal domains, the bent headpiece extends in less than 1 second [1] with intermediate affinity for ligands. Two models- “switchblade” and “deadbolt”- have been proposed for the mechanism of transmission of signals from across the plasma membrane leading to extension (reviewed in [2, 3]).

According to the former model, leg separation causes a jackknife-like extension of the knee that releases the hybrid domain from the constraint of the bent form [4, 5]. The latter model postulates that the activated integrin remains in a bent state (even with bound ligand) until the interaction between the headpiece and the β-stalk is disrupted by piston-like movement of TM domains and sliding of the extracellular stalks [6].

Subsequent opening of the βA/hybrid domain hinge happens by spontaneous swing out of the hybrid domain and thus the integrin dimer becomes competent for ligand binding [7]. In immunologically relevant integrins, serine phosphorylation of integrin α subunit has also been shown as a critical criterion for αI conformation changes for ligand binding [8, 9].

Tension generated by the interplay of cytoskeletal forces and ECM stiffness has been shown to be sufficient for mechanical activation of integrins to aid cell motility [10]. Nevertheless, they are believed to constantly switch between ligand bound active and unbound inactive states, thus conferring the focal adhesions with distinct dynamics so as to endure rapid changes in force [11]. Also, bent integrins that move along the cell membrane may collide with other membrane proteins and this could result in structural changes [12]. However, further structural studies in physiologically relevant conditions are required to substantially establish this theory.

According to the former model, leg separation causes a jackknife-like extension of the knee that releases the hybrid domain from the constraint of the bent form [4, 5]. The latter model postulates that the activated integrin remains in a bent state (even with bound ligand) until the interaction between the headpiece and the β-stalk is disrupted by piston-like movement of TM domains and sliding of the extracellular stalks [6].

Subsequent opening of the βA/hybrid domain hinge happens by spontaneous swing out of the hybrid domain and thus the integrin dimer becomes competent for ligand binding [7]. In immunologically relevant integrins, serine phosphorylation of integrin α subunit has also been shown as a critical criterion for αI conformation changes for ligand binding [8, 9].

Tension generated by the interplay of cytoskeletal forces and ECM stiffness has been shown to be sufficient for mechanical activation of integrins to aid cell motility [10]. Nevertheless, they are believed to constantly switch between ligand bound active and unbound inactive states, thus conferring the focal adhesions with distinct dynamics so as to endure rapid changes in force [11]. Also, bent integrins that move along the cell membrane may collide with other membrane proteins and this could result in structural changes [12]. However, further structural studies in physiologically relevant conditions are required to substantially establish this theory.