Stress Fiber Assembly[Edit]

Content

The mechanisms of stress fiber assembly differ amongst the different types. Stress fibers may be generated through the condensation of small filament fragments, reorganization of pre-existing stress fibers and graded polarity bundles, or by de novo polymerization of actin filaments (reviewed in [1]). One stress fiber type may also convert into another; such is the case when dorsal stress fibers and transverse arcs are converted into ventral stress fibers [2]. Each type of stress fiber may interact with other stress fiber types, and the steps in their formation may involve the same molecular processes.

Transverse Arc Formation[Edit]

Initiation

In general, initiation of stress fiber formation is modulated by signaling cascades involving RhoA small GTPase [3] (reviewed in [4]). Most G-actin polymerization is driven by the actin polymerizing machinery at the barbed end of actin filaments, presumably at the interface between the cell membrane and the underlying filament network abutting the membrane [5, 6]; these barbed ends are created by uncapping or severing existing filaments in the lamellipodium or by de novo nucleation.

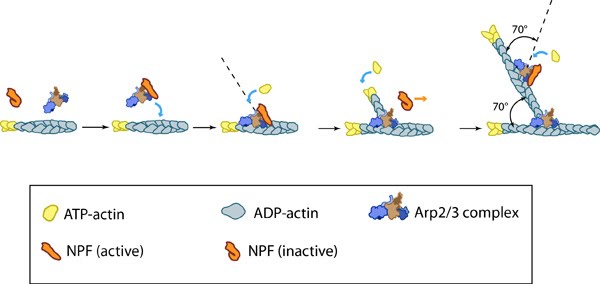

Figure 1. Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization: NPFs (e.g. WASp; Scar) bring together the Arp2/3 complex and actin monomers to nucleate actin filaments that form new branches from the side of preexisting filaments. The Arp2/3 complex remains at the minus end of the filament.

Figure 1. Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization: NPFs (e.g. WASp; Scar) bring together the Arp2/3 complex and actin monomers to nucleate actin filaments that form new branches from the side of preexisting filaments. The Arp2/3 complex remains at the minus end of the filament.The actin filaments in transverse arcs are primarily nucleated in the lamellipodia by the Arp2/3 complex at a position that is parallel to the leading edge [2]. Although effectors of RhoA signaling such as formin (e.g., mDia1) have also been suggested to nucleate actin filaments in stress fibers [7, 8, 9], they are not a primary contributor to transverse arc initiation and assembly [2]. It has been suggested that stress fibers may also form as a result of F-actin stabilization brought about by filament bundling and merging [10]. Consistent with this notion, actin filament bundles in filopodia were found to serve as precursors of arc-like filaments, stress fibers and graded polarity bundles [11, 12].

Most of the initiated filaments in the lamellipodia have their barbed ends facing the nearest cell edge. However, the polarity of the actin filaments becomes mixed as the arcs mature towards the cell center [13]; precisely how this is achieved is unknown.

Assembly

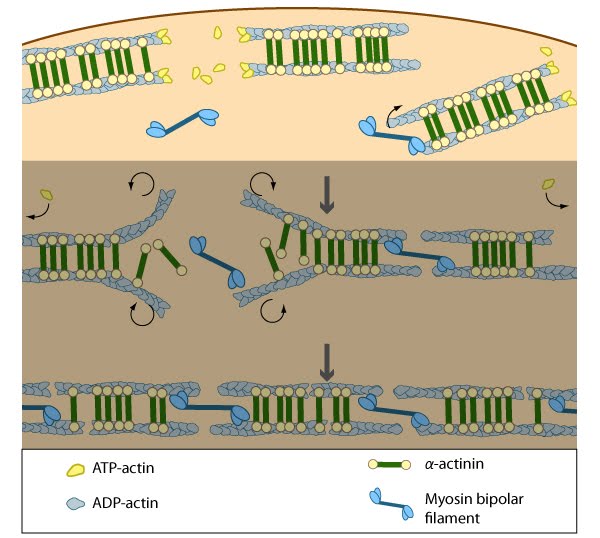

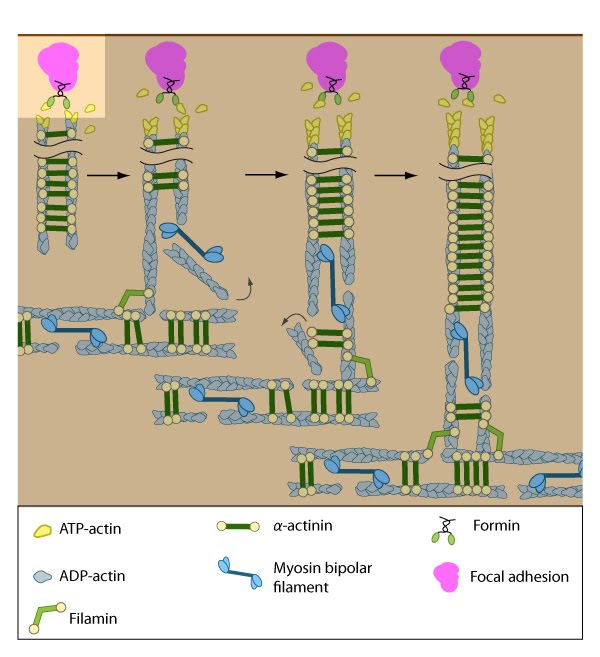

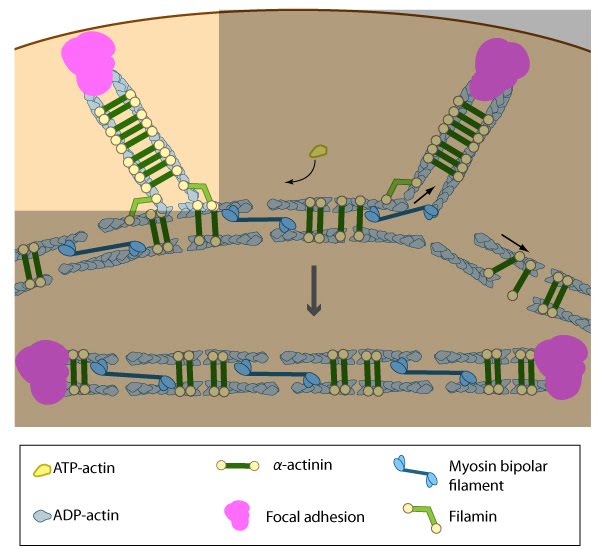

Figure 2. Assembly of transverse arcs: Nascent unipolar filaments are extended and are rapidly bound by actin binding proteins (e.g., α-actinin). The population of filaments steadily exchanges actin subunits and moves towards the cell body due to retrograde actin flow and actin treadmilling; the orientation of the filaments may also change with the direction of movement (figure adapted from [2])

Figure 2. Assembly of transverse arcs: Nascent unipolar filaments are extended and are rapidly bound by actin binding proteins (e.g., α-actinin). The population of filaments steadily exchanges actin subunits and moves towards the cell body due to retrograde actin flow and actin treadmilling; the orientation of the filaments may also change with the direction of movement (figure adapted from [2])As the transverse arc filaments are pulled inward, they are rapidly bound and stabilized by actin binding proteins, such as α-actinin, which crosslinks the arc filaments into small bundles [2]. Similar to other cortical actin networks that are composed of actin bundles (e.g., microvilli, stereocilia), the contraction of transverse arcs at the bundle tip would presumably contribute to: the retrograde flow of actin within the bundle [21, 22]; recruitment of additional proteins (e.g., filamin); and condensation of the transverse arc into larger structures as they are moved towards the cell body [2, 14]. Arc-like bundles may also form from microspikes and filopodia bundles that have been recruited from the lamellipodium in the course of rearward flow [1, 20].

Annealing

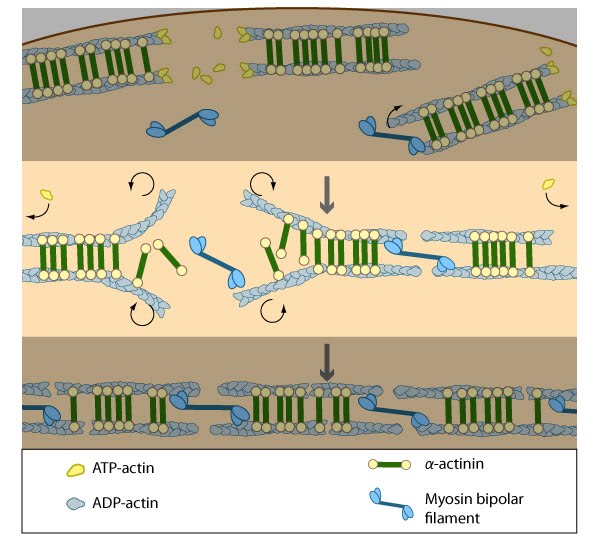

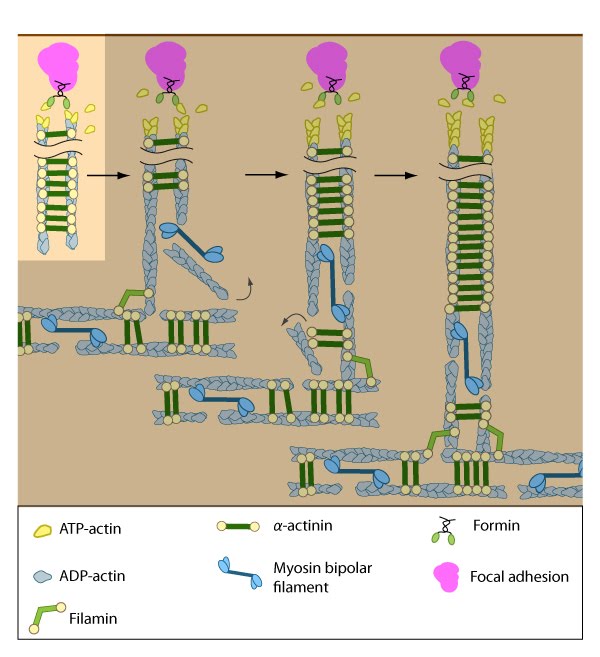

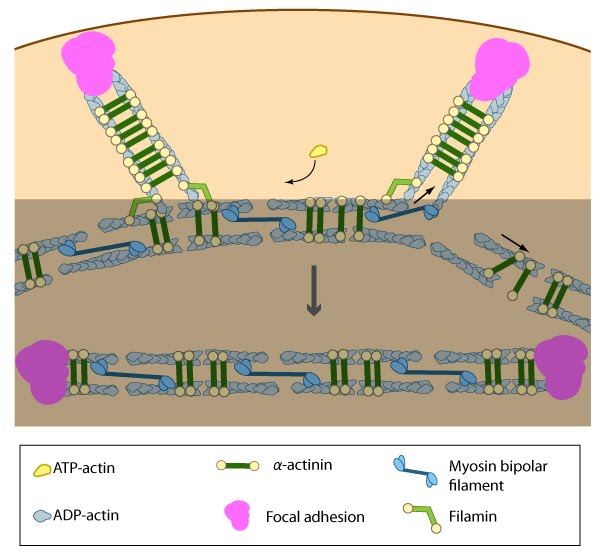

Figure 3. Annealing of transverse arcs: As actin filaments are transported away from the cell edge, they further evolve through end to end annealing and associate with myosin-containing bundles. The filaments undergo continued adjustment and polarity sorting to establish contractile arcs. Actin subunits are exchanged throughout the arcs either as a result of polymerization onto the ends of actin filaments, binding to stress fiber myosin, actin treadmilling or interaction with actin-binding proteins in stress fibers (figure adapted from [2])

Figure 3. Annealing of transverse arcs: As actin filaments are transported away from the cell edge, they further evolve through end to end annealing and associate with myosin-containing bundles. The filaments undergo continued adjustment and polarity sorting to establish contractile arcs. Actin subunits are exchanged throughout the arcs either as a result of polymerization onto the ends of actin filaments, binding to stress fiber myosin, actin treadmilling or interaction with actin-binding proteins in stress fibers (figure adapted from [2])Transverse arcs fully evolve from end-to-end annealing of α-actinin and myosin containing bundles [2]; end-to-end annealing has also been observed in the formation of bundles that resemble ventral stress fibers [10]. It has been suggested that tension generated by the actin–myosin arrangement and myosin II motor activity causes alignment of the actin filaments into these bundles [24, 30] in a manner similar to the reorientation of lamellipodial and filopodial actin filaments during cell migration [31, 11, 12]. Furthermore, in order for stress fibers to be contractile, the unipolar assembly of actin filaments must change to mixed polarity bundles in mature stress fibers [32, 18, 13]; how this is specifically achieved is unknown, but based on experiments using purified components [33], permeabilized cells [34] and live cells [24, 30], it has been suggested that myosin bundles may recruit the filaments and facilitate polarity sorting [35] (reviewed in [1, 36]).

Interestingly, the assembly of transverse arcs and dorsal stress fibers appears to be connected: transverse arcs encounter dorsal stress fibers as they are transported towards the cell body via actin-myosin contractions [2].

Contraction

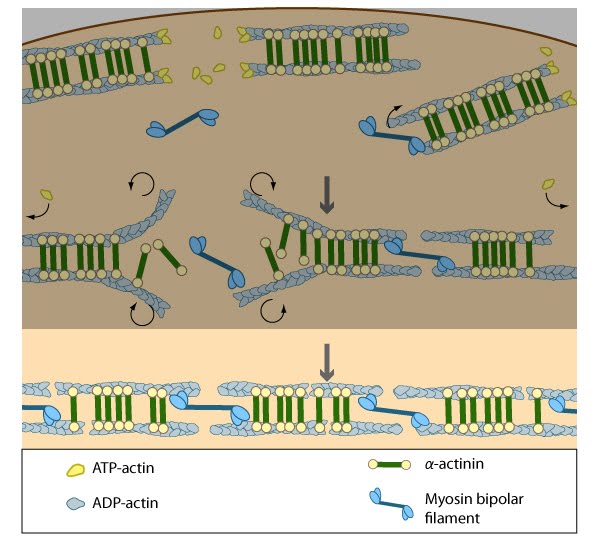

Figure 4. Contraction of transverse arcs: Contraction of the actin-myosin system allows the filaments to adopt a more regular structure that is contractile along its entire length; the extent of actin filament crosslinking may regulate these contractions. Myosin II motor protein activity is necessary for complete transverse arc formation (figure adapted from [2]).

Figure 4. Contraction of transverse arcs: Contraction of the actin-myosin system allows the filaments to adopt a more regular structure that is contractile along its entire length; the extent of actin filament crosslinking may regulate these contractions. Myosin II motor protein activity is necessary for complete transverse arc formation (figure adapted from [2]).Steps in dorsal stress fiber formation[Edit]

Adhesion

Dorsal stress fibers in motile cells are formed from actin filament bundles that are initiated and extended from cell-substrate adhesions at the leading edge (aka focal complexes [FXs]) (reviewed in [46]). S Figure 5. Adhesion of dorsal stress fibers: Soluble clues or binding of cell surface receptors (e.g., integrin) to the substratum components (e.g., fibronectin) promotes clustering of adhesion receptors and subsequent activation of the Rho family of GTPases (e.g., Rac1). Rac1 activity strengthens the nascent adhesion by promoting the assembly of scaffolding proteins and actin-binding proteins to the adhesion site (figure adapted from [2])imilar to graded polarity bundles, retrograde F-aof nectin flow from the leading edge and myosin II activity may be involved in promoting the formation w adhesions [12]; however, new adhesions may also form in a manner that is either force independent or requires relatively low tension [47]. Relative to the migration of the leading edge, the cell-ECM adhesions are static [16]. Nevertheless, stress fiber adhesion components themselves (e.g., α-actinin, vinculin, and talin [48]) are highly plastic and their dynamics are dependent upon mechanotransduction events (reviewed in [46]): as the cell body moves, FX mature into more stable and less dynamic focal adhesions by force-induced structural rearrangements that promote the exchange and addition of new components to the adhesion (reviewed in [49]). In fibroblasts, actin flow appears to cause the formation of “mini-ruffles” and microspike bundles, which may also play a part in forming the initial adhesions found in dorsal or ventral stress fibers [50]. Inhibition of focal adhesions assembly blocks stress fiber formation in general [10].

Figure 5. Adhesion of dorsal stress fibers: Soluble clues or binding of cell surface receptors (e.g., integrin) to the substratum components (e.g., fibronectin) promotes clustering of adhesion receptors and subsequent activation of the Rho family of GTPases (e.g., Rac1). Rac1 activity strengthens the nascent adhesion by promoting the assembly of scaffolding proteins and actin-binding proteins to the adhesion site (figure adapted from [2])imilar to graded polarity bundles, retrograde F-aof nectin flow from the leading edge and myosin II activity may be involved in promoting the formation w adhesions [12]; however, new adhesions may also form in a manner that is either force independent or requires relatively low tension [47]. Relative to the migration of the leading edge, the cell-ECM adhesions are static [16]. Nevertheless, stress fiber adhesion components themselves (e.g., α-actinin, vinculin, and talin [48]) are highly plastic and their dynamics are dependent upon mechanotransduction events (reviewed in [46]): as the cell body moves, FX mature into more stable and less dynamic focal adhesions by force-induced structural rearrangements that promote the exchange and addition of new components to the adhesion (reviewed in [49]). In fibroblasts, actin flow appears to cause the formation of “mini-ruffles” and microspike bundles, which may also play a part in forming the initial adhesions found in dorsal or ventral stress fibers [50]. Inhibition of focal adhesions assembly blocks stress fiber formation in general [10].

Figure 5. Adhesion of dorsal stress fibers: Soluble clues or binding of cell surface receptors (e.g., integrin) to the substratum components (e.g., fibronectin) promotes clustering of adhesion receptors and subsequent activation of the Rho family of GTPases (e.g., Rac1). Rac1 activity strengthens the nascent adhesion by promoting the assembly of scaffolding proteins and actin-binding proteins to the adhesion site (figure adapted from [2])

Figure 5. Adhesion of dorsal stress fibers: Soluble clues or binding of cell surface receptors (e.g., integrin) to the substratum components (e.g., fibronectin) promotes clustering of adhesion receptors and subsequent activation of the Rho family of GTPases (e.g., Rac1). Rac1 activity strengthens the nascent adhesion by promoting the assembly of scaffolding proteins and actin-binding proteins to the adhesion site (figure adapted from [2])Initiation

Figure 6. Initiation of dorsal stress fibers: Rho GTPases promote signal transduction cascades and interact directly with components of the actin polymerizing module to initiate actin filament assembly. Actin filaments in dorsal stress fibers are primarily initiated by formin-mediated nucleation (e.g., mDia1) (figure adapted from [2]).

Figure 6. Initiation of dorsal stress fibers: Rho GTPases promote signal transduction cascades and interact directly with components of the actin polymerizing module to initiate actin filament assembly. Actin filaments in dorsal stress fibers are primarily initiated by formin-mediated nucleation (e.g., mDia1) (figure adapted from [2]).The short unipolar actin filaments in dorsal stress fibers are polymerized and elongated from focal adhesions via a formin-dependent mechanism (e.g., mDia1/DRF1) [2]. This leaves the barbed ends of the actin filaments directed towards the adhesion (reviewed in [54]). The enzymatic activity of Rac, Rho, and their effectors (e.g., ROCK) is necessary to recruit formins to focal adhesions, where they are thought to play a vital role in creating a stable pool of cortical actin and in maintaining free filament barbed ends [55, 56, 57].

The elasticity of formins at focal adhesions may be tied to their mechanosensing ability, as suggested by increased force-induced actin polymerization at these adhesive sites [58]. Several studies also show that actin filament bundles in filopodia can serve as precursors of dorsal stress fibers or graded polarity bundles [11, 12]. Certain groups that did not observe actin polymerization during stress fiber formation have suggested that stress fibers may form as a result of F-actin stabilization brought about by filament bundling and merging [10].

Assembly

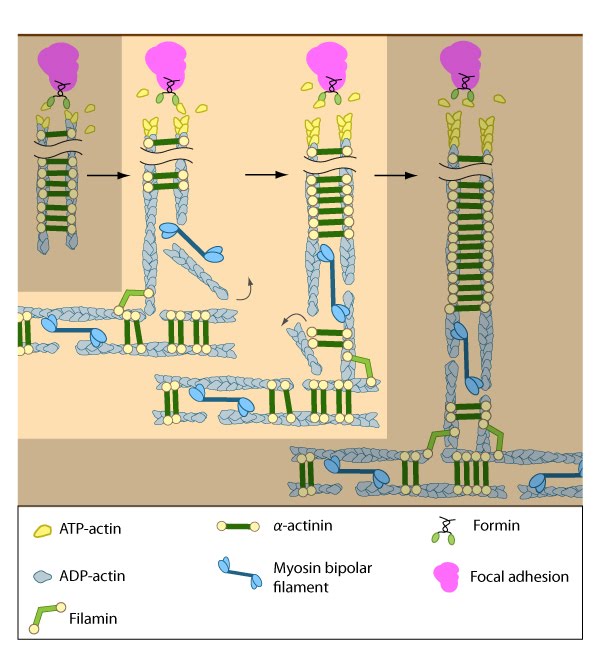

Figure 7. Assembly of dorsal stress fibers: The nascent adhesions continue to grow and exchange components. Nascent unipolar actin filaments are extended and they are stabilized by actin binding proteins (e.g., α-actinin, filamin). The population of filaments are crosslinked into bundles and they steadily exchange actin subunits as they move towards the cell body due to retrograde actin flow and actin treadmilling. The orientation and polarity of the filaments may become mixed as they are transported (figure adapted from [2]).

Figure 7. Assembly of dorsal stress fibers: The nascent adhesions continue to grow and exchange components. Nascent unipolar actin filaments are extended and they are stabilized by actin binding proteins (e.g., α-actinin, filamin). The population of filaments are crosslinked into bundles and they steadily exchange actin subunits as they move towards the cell body due to retrograde actin flow and actin treadmilling. The orientation and polarity of the filaments may become mixed as they are transported (figure adapted from [2]). Figure 8. Incorporation of dorsal stress fibers: Dorsal stress fibers (DSF) appear to contact transverse arcs at their proximal ends towards the cell body. DSF are thought to ‘feed’ the transverse arcs with filaments of mixed polarity. Although myosin II bundles are generally absent from DSF, occasionally they will displace α-actinin and become incorporated towards the proximal end of DSF (figure adapted from [33]).

Figure 8. Incorporation of dorsal stress fibers: Dorsal stress fibers (DSF) appear to contact transverse arcs at their proximal ends towards the cell body. DSF are thought to ‘feed’ the transverse arcs with filaments of mixed polarity. Although myosin II bundles are generally absent from DSF, occasionally they will displace α-actinin and become incorporated towards the proximal end of DSF (figure adapted from [33]).Similar to other cortical actin networks that are composed of actin bundles (e.g., microvilli, stereocilia), the elongation of filaments from the base of the adhesion would presumably contribute to the retrograde flow of actin away from the adhesion and promote the condensation of the dorsal fiber into larger bundles as they are moved towards the cell body [2, 21 , 22]. The filament orientation may also change despite the adhesion site remaining stationary relative to the substrate [16]. Dorsal stress fibers can also be connected to transverse arcs in the cell body where the transverse arcs filaments are suggested to continuously supply the dorsal stress fibers with actin filaments [1]. Precisely how this is achieved, is unknown (reviewed in [36]); however, it likely involves actin binding proteins and myosin motor activity.

Incorporation

Interestingly, the assembly of dorsal stress fibers and transverse arcs appears to be connected: transverse arcs encounter dorsal stress fibers as they are transported towards the cell body via cell-wide actin–myosin contractions [2]. The unipolar filaments in dorsal stress fibers are typically non-contractile (at least in the human U2OS bone cell line); however, because their proximal ends are connected to transverse arcs, myosin II is occasionally incorporated into the ends of the DSF, simultaneously displacing α-actinin in this process [2]. The connection to transverse arcs and maturation of elongating dorsal stress fibers (in terms of length) seem to be prerequisites for the incorporation of myosin into dorsal stress fibers [2]. Transverse arcs are also thought to continuously supply dorsal stress fibers with actin filaments as they retract centripetally (reviewed in [1]). Exactly how transverse arcs filaments are fed into dorsal stress fibers is unknown, but based on experiments using purified components [33], mathematical models, and live cells [61, 30], it has been suggested that myosin bundles may recruit the filaments and facilitate polarity sorting [35] (reviewed in [1, 36]). In line with this concept, factors that regulate myosin bundle formation (e.g., myosin light chain kinase [62], Rho-associated kinase [63]) or their binding to stress fiber actin filaments (e.g., tropomyosin [64]) will likely contribute to incorporation of dorsal stress fibers.

Although transverse arcs are not connected directly to focal adhesions, the contractile tension generated by transverse arcs presumably can be transmitted to the cell surface and transferred to the substrate through the dorsal stress fibers; whether this predicted force transmission actually leads to extracellular remodeling, is relatively unexplored.

Steps in ventral stress fiber formation[Edit]

Formation of ventral stress fibers

Figure 9. Formation of ventral stress fibers: Actin filaments in ventral stress fibers are originally created either de novo or by extending pre-existing filaments. The filaments are anchored to focal adhesions and crosslinked into bundles by components of the actin linking module (e.g., α-actinin, filamin).

Figure 9. Formation of ventral stress fibers: Actin filaments in ventral stress fibers are originally created either de novo or by extending pre-existing filaments. The filaments are anchored to focal adhesions and crosslinked into bundles by components of the actin linking module (e.g., α-actinin, filamin).Association of ventral stress fibers

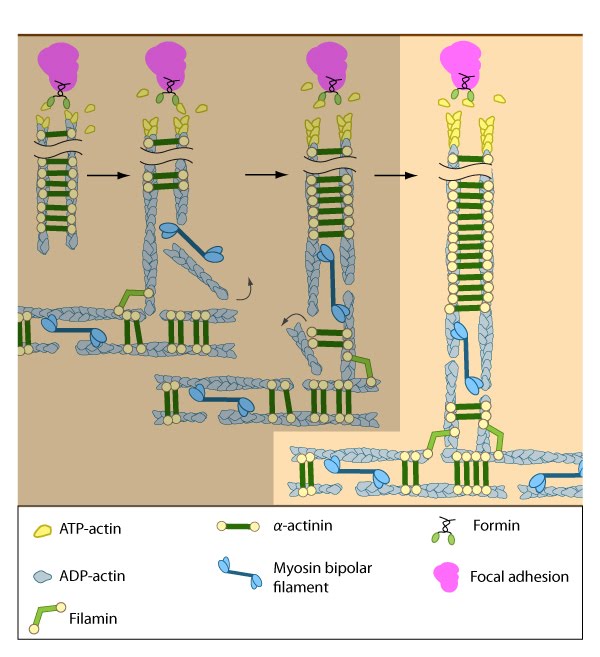

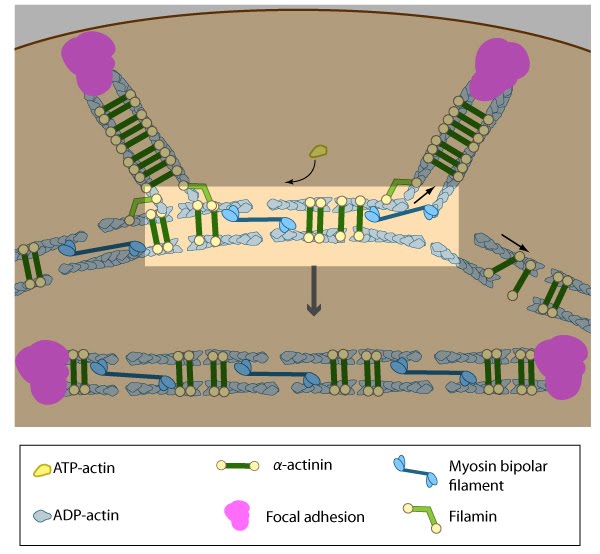

Figure 10. Association of ventral stress fibers: Pre-existing dorsal stress fibers interact with transverse arcs to demarcate a region of the arc that will align between the two dorsal stress fibers. Crosslinking of the actin filaments by actin binding proteins assistss this interaction. Actin subunits are exchanged throughout the stress fibers and arcs either as a result of polymerization onto the ends of actin filaments, binding to stress fiber myosin, actin treadmilling or interaction with actin-binding proteins in stress fibers (figure adapted from [2]).

Figure 10. Association of ventral stress fibers: Pre-existing dorsal stress fibers interact with transverse arcs to demarcate a region of the arc that will align between the two dorsal stress fibers. Crosslinking of the actin filaments by actin binding proteins assistss this interaction. Actin subunits are exchanged throughout the stress fibers and arcs either as a result of polymerization onto the ends of actin filaments, binding to stress fiber myosin, actin treadmilling or interaction with actin-binding proteins in stress fibers (figure adapted from [2]).Many actin binding proteins that are found along stress fibers or at their distal adhesions (e.g., α-actinin,filamin, zyxin, talin, vinculin, espin [65], caldesmon [65]) are mechanosensitive and they are known to regulate the structure of the actin cytoskeleton (reviewed in [46, 66, 67, 68, 69, 29]). Unfortunately, their exact function in stress fibers is relatively unknown. Ventral stress fibers association likely involves a dynamic interplay between number of actin binding proteins and myosin motors within the filament bundles.

Alignment of ventral stress fibers

Figure 11. Alignment of ventral stress fibers: The pre-existing dorsal stress fibers interface with the transverse arcs which leaves the arc filaments aligned between the two dorsal stress fibers. Myosin bundles donated by the transverse arc continue to contract, which helps bring the fused structure into complete alignment.

Figure 11. Alignment of ventral stress fibers: The pre-existing dorsal stress fibers interface with the transverse arcs which leaves the arc filaments aligned between the two dorsal stress fibers. Myosin bundles donated by the transverse arc continue to contract, which helps bring the fused structure into complete alignment.Contraction of ventral stress fibers

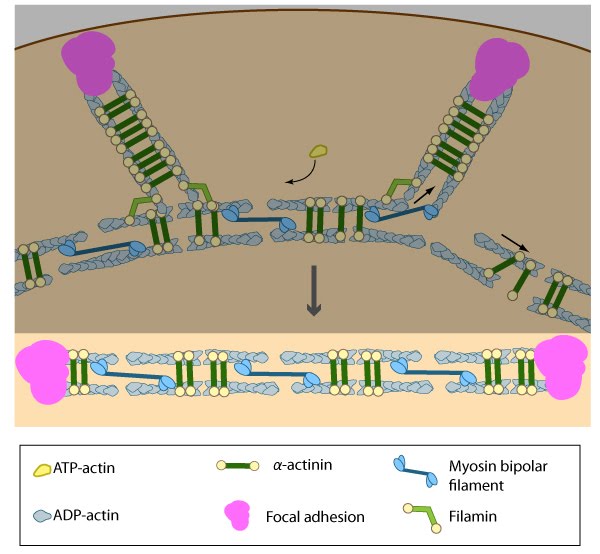

Figure 12. Contraction of ventral stress fibers: Once the actin filaments and myosin bundles are aligned, contractile activity along the filaments further organizes the bundles and brings the stress fiber to a completely ‘fused’ state: the completed ventral stress fiber is anchored by focal adhesions at both ends and the contractile bundles are dispersed throughout.

Figure 12. Contraction of ventral stress fibers: Once the actin filaments and myosin bundles are aligned, contractile activity along the filaments further organizes the bundles and brings the stress fiber to a completely ‘fused’ state: the completed ventral stress fiber is anchored by focal adhesions at both ends and the contractile bundles are dispersed throughout.Once the actin bundles are aligned and completely ‘fused’, the completed ventral stress fiber is anchored by focal adhesions at both ends and the contractile bundles are dispersed throughout. Although stress fibers appear to contract continuously, the contractions are not uniform along their entire length [70] and the contraction strength varies with the adhesion strength (at least in muscle fibroblasts [71]). The extent of contraction also directly correlates with altered transcription of certain genes [38].

Contractile activity on a whole-cell level will influence the structural organization of the cytoskeleton and stress fiber stability/activity in ways that impact the cell morphology. For example, both contraction strength [38, 39, 40] and regulation of myosin II activity [41] correlate with stress fiber formation and they regulate the overall stability and integrity of stress fibers [42, 43, 31, 44]. There is also a reciprocal relationship between the strength of contractions and changes in cell morphology: cell morphology contributes to the formation of stress fibers and the resulting magnitude of contractile force that can be generated [45], while in reverse, the extent of contractions will influence the cell morphology [38]. These examples underscore the importance of elucidating the mechanisms and molecules responsible for integrating and regulating contractile activity in stress fibers.