Stress Fiber

What are stress fibers?[Edit]

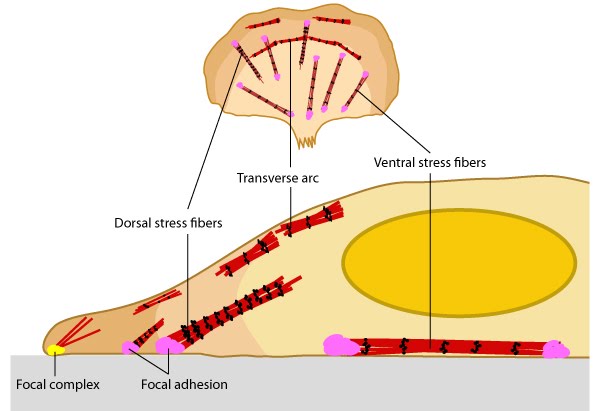

Stress fibers are higher order cytoskeletal structures composed of cross-linked actin filament bundles, and in many cases, myosin motor proteins, that span a length of 1-2 micrometers [1]. At least 4 types of stress fibers have been identified in mammalian cells [2]. These are dorsal stress fibers, ventral stress fibers, transverse arcs, and the recently identified perinuclear actin cap, which is an important mediator in nuclear mechanotransduction. Each type of stress fiber is defined by their location in the cell, their morphology and their function at focal adhesions (reviewed in [3]). The presence of motor proteins in stress fibers enables contractility – an important factor in stress fiber function and in cell motility. In most cases, stress fibers connect to focal adhesions, and hence are crucial in mechanostransduction. In mammalian cells, stress fibers undergo continuous assembly and disassembly. This allows them to maintain cellular tension and undergo modification in response to various forces (e.g., mechanical stress [4, 5]).

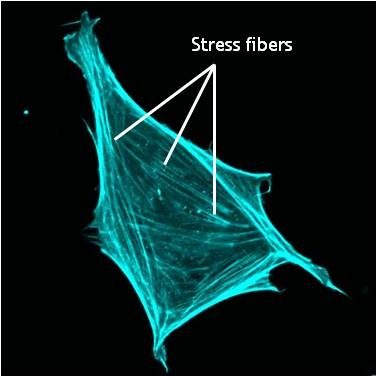

Figure 1. Stress fibers in a cell labeled for F-actin: A mouse embryonic fibroblast of the RPTPa cell line, plated on a fibronectin coated glass cover slip. The cell was transfected with RFP-Lifeact (a kind gift from Dr Roland Wedlich-Soldner, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Germany), which labels F-actin in living cells. The cell was imaged using a Nikon A1Rsi confocal microscope at 60x magnification and false coloured cyan. Image captured by Wei Wei Luo, Mechanobiology Institute, Singapore.

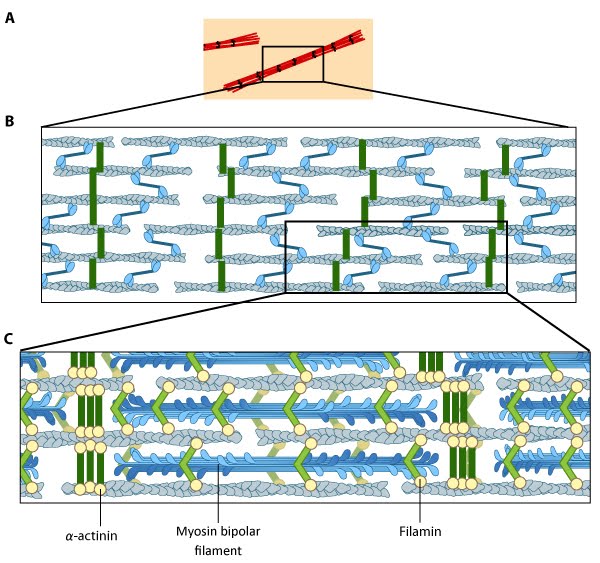

Figure 1. Stress fibers in a cell labeled for F-actin: A mouse embryonic fibroblast of the RPTPa cell line, plated on a fibronectin coated glass cover slip. The cell was transfected with RFP-Lifeact (a kind gift from Dr Roland Wedlich-Soldner, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Germany), which labels F-actin in living cells. The cell was imaged using a Nikon A1Rsi confocal microscope at 60x magnification and false coloured cyan. Image captured by Wei Wei Luo, Mechanobiology Institute, Singapore. Figure 2. Stress fiber structure: A. Isolated stress fibers have a banded appearance, with bundles of actin filaments interspersed with semiperiodic electron-dense regions. B. The electron-dense regions are rich in actin crosslinking proteins, namely α-actinin. Bipolar myosin II filaments lie between the loosely packed actin filaments in the regions that lack α-actinin . C. A high resolution view of the bipolar myosin filament heads interspersed between the regions rich in α-actinin. Relative to α-actinin, the more flexible actin crosslinking protein, filamin, is dispersed throughout the entire stress fiber.

Figure 2. Stress fiber structure: A. Isolated stress fibers have a banded appearance, with bundles of actin filaments interspersed with semiperiodic electron-dense regions. B. The electron-dense regions are rich in actin crosslinking proteins, namely α-actinin. Bipolar myosin II filaments lie between the loosely packed actin filaments in the regions that lack α-actinin . C. A high resolution view of the bipolar myosin filament heads interspersed between the regions rich in α-actinin. Relative to α-actinin, the more flexible actin crosslinking protein, filamin, is dispersed throughout the entire stress fiber.Types of Stress Fibers[Edit]

Transverse arcs (TAs) are found only in cells that are actively protrusive. TA appear as curved bundles of actin and myosin filaments behind the lamella. Unlike the ventral fibers, TAs do not interact directly with focal adhesions (FA). TAs have been implicated in actin retrograde flow from the leading edge to the cell center where they are disassembled [17].

Dorsal stress fibers (DSF) are the main transmitters of contractile forces (as opposed to producers) to the underlying substrate. They attach to FAs at the base of the cell then rise towards the dorsal surface to form a loose matrix of actin filaments [18]. DSF often terminate at a TA at their proximal end. It is important to note that DSF are suggested to serve as precursors of VSF and do not exhibit periodic distribution of α-actinin and myosin on the filaments (aka contractile bundle), so their identity as stress fibers has been debated (reviewed in [3]).

Ventral stress fibers (VSF) are filament bundles located at the ventral surface of the cell that are attached to FAs at each end of the bundle; these stress fibers extend from FAs close to the cell edge (i.e. lamellipodia) to an adhesion behind or near the nucleus (reviewed in [19]). The VSF are fundamental to tail retraction and cell shape changes during cell migration [20] and on their sides they can structure cell borders against inward pressure of the membrane [21].

Dorsal stress fibers (DSF) are the main transmitters of contractile forces (as opposed to producers) to the underlying substrate. They attach to FAs at the base of the cell then rise towards the dorsal surface to form a loose matrix of actin filaments [18]. DSF often terminate at a TA at their proximal end. It is important to note that DSF are suggested to serve as precursors of VSF and do not exhibit periodic distribution of α-actinin and myosin on the filaments (aka contractile bundle), so their identity as stress fibers has been debated (reviewed in [3]).

Ventral stress fibers (VSF) are filament bundles located at the ventral surface of the cell that are attached to FAs at each end of the bundle; these stress fibers extend from FAs close to the cell edge (i.e. lamellipodia) to an adhesion behind or near the nucleus (reviewed in [19]). The VSF are fundamental to tail retraction and cell shape changes during cell migration [20] and on their sides they can structure cell borders against inward pressure of the membrane [21].

Stress Fiber Activity[Edit]

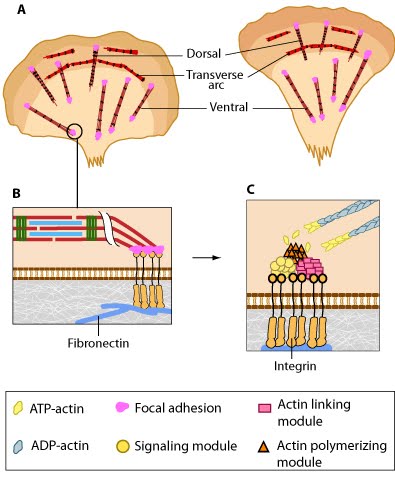

Stress fibers are contractile in nature. By exerting and maintaining tension on the underlying substratum, they form a key element of the mechanotransduction apparatus that links the cell interior and exterior.  Figure 4. Stress fibers link the cell interior to the exterior through focal adhesions: A. Stress fibers in slowly migrating cells, e.g., bone cancer cells (left) and fibroblasts (right). B. The presence of myosin thick filaments in stress fibers and transverse arcs makes them contractile. C. Dorsal/ventral stress fibers are anchored to the external surface through the focal adhesions. Assembly of over 165 component molecules into the FA is modulated by internal forces from the contraction of myosin and actin filaments in the stress fiber, or external forces generated on ECM components.The organization of stress fibers resembles the alternating thick actin filaments and Z bands in muscle myofibrils, however, the actin and myosin filaments in stress fibers are less regular when compared to myofibrils [1] and they do not contract uniformly along their lengths [12]. Similar to muscle cells, the myosin motor proteins hydrolyse ATP and their coordinated movement along the complex of actin filaments causes the filaments to slide past each other, which translates into shortening or contraction of the stress fiber by as much as 20% [22]. Cell-generated tension allows stress fibers to stabilize the cell structure, produce force, and transduce mechanical information about the composition of the cell exterior to drive changes in cell shape, migration, and ECM remodeling (reviewed in [23]).

Stress fibers appear to contract continuously with occasional relaxing or stretching; this contraction force is mediated by a class of non-processive, ATP-dependent myosin motor proteins [24]. ATP hydrolysis allows the myosin protein to undergo a conformational change that results in the movement of the actin filament relative to myosin in order to generate force. Each ATP hydrolysis allows a displacement of 5-25 nm [24], however, it is important to highlight that stress fibers require anchorage in order to exert this force. Stress fibers are linked at either end to the cell exterior by a large assembly of proteins known as the focal adhesion (FA). Both traction forces and resting tension that are produced by the contraction of the stress fibers are fundamental for force generation and are essential for regulating cell shape, adhesion and motility [24].

Figure 4. Stress fibers link the cell interior to the exterior through focal adhesions: A. Stress fibers in slowly migrating cells, e.g., bone cancer cells (left) and fibroblasts (right). B. The presence of myosin thick filaments in stress fibers and transverse arcs makes them contractile. C. Dorsal/ventral stress fibers are anchored to the external surface through the focal adhesions. Assembly of over 165 component molecules into the FA is modulated by internal forces from the contraction of myosin and actin filaments in the stress fiber, or external forces generated on ECM components.The organization of stress fibers resembles the alternating thick actin filaments and Z bands in muscle myofibrils, however, the actin and myosin filaments in stress fibers are less regular when compared to myofibrils [1] and they do not contract uniformly along their lengths [12]. Similar to muscle cells, the myosin motor proteins hydrolyse ATP and their coordinated movement along the complex of actin filaments causes the filaments to slide past each other, which translates into shortening or contraction of the stress fiber by as much as 20% [22]. Cell-generated tension allows stress fibers to stabilize the cell structure, produce force, and transduce mechanical information about the composition of the cell exterior to drive changes in cell shape, migration, and ECM remodeling (reviewed in [23]).

Stress fibers appear to contract continuously with occasional relaxing or stretching; this contraction force is mediated by a class of non-processive, ATP-dependent myosin motor proteins [24]. ATP hydrolysis allows the myosin protein to undergo a conformational change that results in the movement of the actin filament relative to myosin in order to generate force. Each ATP hydrolysis allows a displacement of 5-25 nm [24], however, it is important to highlight that stress fibers require anchorage in order to exert this force. Stress fibers are linked at either end to the cell exterior by a large assembly of proteins known as the focal adhesion (FA). Both traction forces and resting tension that are produced by the contraction of the stress fibers are fundamental for force generation and are essential for regulating cell shape, adhesion and motility [24].

Not surprisingly, stress fibers are less evident in actively migrating cells. In line with this observation, when a cultured fibroblast is removed from the substratum, it adopts a spherical morphology, coupled with the disappearance of stress fibers. When the cell is returned to the substratum, the stress fibers reappear within hours. Stress fibers are rarely observed in cells and tissues in vivo, thus many groups claim that stress fibers are an artefact of in vitro artificial culture. However, recent studies demonstrated that stress fibers play an important role in vivo: for example, in the closure of epithelial sheets during embryogenesis, in contraction of myoepithelial cells around many epithelial ducts, and in endothelial cells of blood vessels [14]. Furthermore, muscle cell myofibrils form from stress fiber like precursors during myofibrillogenesis [25].

Figure 4. Stress fibers link the cell interior to the exterior through focal adhesions: A. Stress fibers in slowly migrating cells, e.g., bone cancer cells (left) and fibroblasts (right). B. The presence of myosin thick filaments in stress fibers and transverse arcs makes them contractile. C. Dorsal/ventral stress fibers are anchored to the external surface through the focal adhesions. Assembly of over 165 component molecules into the FA is modulated by internal forces from the contraction of myosin and actin filaments in the stress fiber, or external forces generated on ECM components.

Figure 4. Stress fibers link the cell interior to the exterior through focal adhesions: A. Stress fibers in slowly migrating cells, e.g., bone cancer cells (left) and fibroblasts (right). B. The presence of myosin thick filaments in stress fibers and transverse arcs makes them contractile. C. Dorsal/ventral stress fibers are anchored to the external surface through the focal adhesions. Assembly of over 165 component molecules into the FA is modulated by internal forces from the contraction of myosin and actin filaments in the stress fiber, or external forces generated on ECM components.Not surprisingly, stress fibers are less evident in actively migrating cells. In line with this observation, when a cultured fibroblast is removed from the substratum, it adopts a spherical morphology, coupled with the disappearance of stress fibers. When the cell is returned to the substratum, the stress fibers reappear within hours. Stress fibers are rarely observed in cells and tissues in vivo, thus many groups claim that stress fibers are an artefact of in vitro artificial culture. However, recent studies demonstrated that stress fibers play an important role in vivo: for example, in the closure of epithelial sheets during embryogenesis, in contraction of myoepithelial cells around many epithelial ducts, and in endothelial cells of blood vessels [14]. Furthermore, muscle cell myofibrils form from stress fiber like precursors during myofibrillogenesis [25].