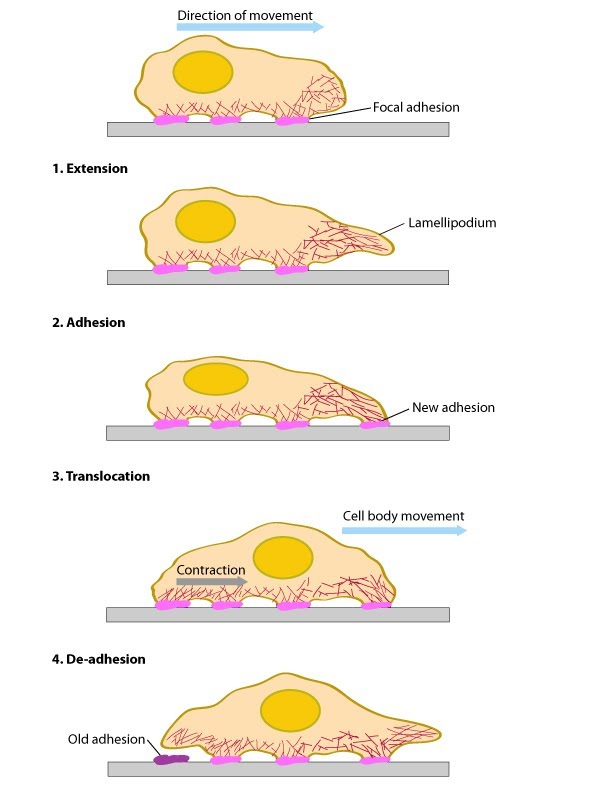

Steps in Formation 1. Initiation and Nucleation 2. Extension, Pause and Stasis 3. Formation of Adhesions 4. Force Generation and Translocation 5. Disassembly of actin filaments and retraction of the trailing edge Functional Modules

| Lamellipodia and Lamella

Steps in Formation: Overview

|

References:

1. Oliver T, Dembo M & Jacobson K. Separation of propulsive and adhesive traction stresses in locomoting keratocytes. J Cell Biol 1999, 145:589-604. [PubMedID: 10225959]2. Elson EL, Felder SF, Jay PY, Kolodney MS & Pasternak C. Forces in cell locomotion. Biochem Soc Symp 1999, 65:299-314. [PubMedID: 10320946]

3. Theriot JA. The polymerization motor. Traffic 2000, 1:19-28. [PubMedID: 11208055]

4. Loisel TP, Boujemaa R, Pantaloni D & Carlier MF. Reconstitution of actin-based motility of Listeria and Shigella using pure proteins. Nature 1999, 401:613-616. DOI: 10.1038/44183; [PubMedID: 10524632]

5. Dubin-Thaler BJ, Hofman BJ, Jake M, Cai Y, Xenias H, Spielman I, Shneidman AV, David LA, Döbereiner HG, Wiggins CH, & Sheetz MP. Quantification of cell edge velocities and traction forces reveals distinct motility modules during cell spreading. PLoS ONE 2008, 3:e3735. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003735; [PubMedID: 19011687]

6. Ponti A, Machacek M, Gupton SL, Waterman-Storer CM & Danuser G. Two distinct actin networks drive the protrusion of migrating cells. Science 2004, 305:1782-1786. DOI: 10.1126/science.1100533; [PubMedID: 15375270]

7. Gupton SL & Waterman-Storer CM. Spatiotemporal feedback between actomyosin and focal-adhesion systems optimizes rapid cell migration. Cell 2006, 125:1361-1374. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.029; [PubMedID: 16814721]

8. Giannone G et al.. Lamellipodial actin mechanically links myosin activity with adhesion-site formation. Cell 2007, 128:561-575. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.039; [PubMedID: 17289574]

9. Schaub S, Bohnet S, Laurent VM, Meister JJ & Verkhovsky AB. Comparative maps of motion and assembly of filamentous actin and myosin II in migrating cells. Mol Biol Cell 2007, 18:3723-3732. DOI: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0859; [PubMedID: 17634292]

10. Carlier MF, Le Clainche C, Wiesner S & Pantaloni D. Actin-based motility: from molecules to movement. Bioessays 2003, 25:336-345. DOI: 10.1002/bies.10257; [PubMedID: 12655641]

11. Pollard TD & Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell 2003, 112:453-465. [PubMedID: 12600310]

12. Le Clainche C & Carlier MF. Regulation of actin assembly associated with protrusion and adhesion in cell migration. Physiol Rev 2008, 88:489-513. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2007; [PubMedID: 18391171]

13. Lock JG, Wehrle-Haller B & Strömblad S. Cell-matrix adhesion complexes: master control machinery of cell migration. Semin Cancer Biol 2008, 18:65-76. DOI: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.10.001; [PubMedID: 18023204]

14. Dalby MJ, Riehle MO, Sutherland DS, Agheli H & Curtis ASG. Morphological and microarray analysis of human fibroblasts cultured on nanocolumns produced by colloidal lithography. Eur Cell Mater 2005, 9:1-8; discussion 8. [PubMedID: 15690263]

15. Döbereiner HG, Dubin-Thaler BJ, Hofman JM, Xenias HS, Sims TN, Giannone G, Dustin ML, Wiggins CH & Sheetz MP. Lateral membrane waves constitute a universal dynamic pattern of motile cells. Phys Rev Lett 2006, 97:038102. [PubMedID: 16907546]

16. Alexandrova AY, Arnold K, Schaub S, Vasiliev JM, Meister JJ, Bershadsky AD & Verkhovsky AB. Comparative dynamics of retrograde actin flow and focal adhesions: formation of nascent adhesions triggers transition from fast to slow flow. PloS one 2008, 3:e3234. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003234; [PubMedID: 18800171]

17. Tsukada Y, Aoki K, Nakamura T, Sakumura Y, Matsuda M & Ishii S. Quantification of local morphodynamics and local GTPase activity by edge evolution tracking. PLoS Comput Biol 2008, 4:e1000223. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000223; [PubMedID: 19008941]

18. Vogel V & Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2006, 7:265-275. DOI: 10.1038/nrm1890; [PubMedID: 16607289]

19. Shutova MS, Alexandrova AY & Vasiliev JM. Regulation of polarity in cells devoid of actin bundle system after treatment with inhibitors of myosin II activity. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 2008, 65:734-746. DOI: 10.1002/cm.20295; [PubMedID: 18615701]