Unit 5: Cell-Matrix Adhesions Functional Modules

Additional Resources Test Your Knowledge Cell-Matrix Adhesions Quiz | Cell-Matrix Adhesions5.4 Initiation of Focal Adhesion Assembly

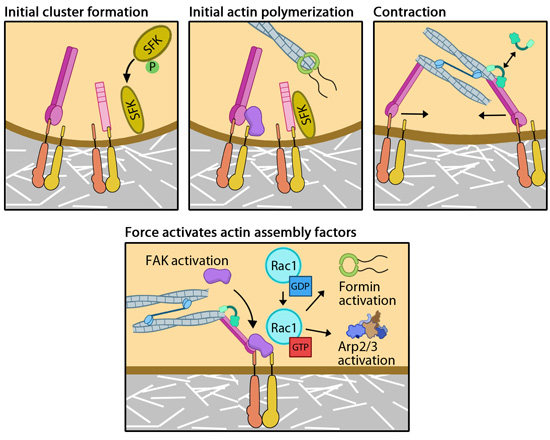

Focal adhesion formation is initiated upon the binding of adhesion receptors to extracellular matrix (ECM) ligands (e.g. fibronectin, vitronectin, collagen) along the cell periphery usually at the protruding edge of a cell. Both intracellular and extracellular factors can influence the level of matrix binding, in terms of affinity (the strength of interactions, reviewed in [1, 2]) and avidity (the number of interactions, such as lateral interactions between independently activated proteins within a focal adhesion). Nascent focal adhesions first appear exclusively in the lamellipodium as submicron-sized puncta that are typically immobile but can at times travel short distances along the direction of the actin retrograde flow [3, 4].

|

References

- Calderwood DA. Integrin activation. J. Cell. Sci. 2004; 117(Pt 5):657-66. [PMID: 14754902]

- Harburger DS. & Calderwood DA. Integrin signalling at a glance. J. Cell. Sci. 2009; 122(Pt 2):159-63. [PMID: 19118207]

- Alexandrova AY., Arnold K., Schaub S., Vasiliev JM., Meister JJ., Bershadsky AD. & Verkhovsky AB. Comparative dynamics of retrograde actin flow and focal adhesions: formation of nascent adhesions triggers transition from fast to slow flow. PLoS ONE 2008; 3(9):e3234. [PMID: 18800171]

- Choi CK., Vicente-Manzanares M., Zareno J., Whitmore LA., Mogilner A. & Horwitz AR. Actin and alpha-actinin orchestrate the assembly and maturation of nascent adhesions in a myosin II motor-independent manner. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008; 10(9):1039-50. [PMID: 19160484]

- Kong F., García AJ., Mould AP., Humphries MJ. & Zhu C. Demonstration of catch bonds between an integrin and its ligand. J. Cell Biol. 2009; 185(7):1275-84. [PMID: 19564406]

- Friedland JC., Lee MH. & Boettiger D. Mechanically activated integrin switch controls alpha5beta1 function. Science 2009; 323(5914):642-4. [PMID: 19179533]

- Nishizaka T., Shi Q. & Sheetz MP. Position-dependent linkages of fibronectin- integrin-cytoskeleton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000; 97(2):692-7. [PMID: 10639141]

- Puklin-Faucher E. & Sheetz MP. The mechanical integrin cycle. J. Cell. Sci. 2009; 122(Pt 2):179-86. [PMID: 19118210]

- Laukaitis CM., Webb DJ., Donais K. & Horwitz AF. Differential dynamics of alpha 5 integrin, paxillin, and alpha-actinin during formation and disassembly of adhesions in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 2001; 153(7):1427-40. [PMID: 11425873]

- Zaidel-Bar R., Cohen M., Addadi L. & Geiger B. Hierarchical assembly of cell-matrix adhesion complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2004; 32(Pt3):416-20. [PMID: 15157150]

- Roca-Cusachs P., Gauthier NC., Del Rio A. & Sheetz MP. Clustering of alpha(5)beta(1) integrins determines adhesion strength whereas alpha(v)beta(3) and talin enable mechanotransduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009; 106(38):16245-50. [PMID: 19805288]

- Blystone SD., Slater SE., Williams MP., Crow MT. & Brown EJ. A molecular mechanism of integrin crosstalk: alphavbeta3 suppression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates alpha5beta1 function. J. Cell Biol. 1999; 145(4):889-97. [PMID: 10330414]

- Tolias KF., Cantley LC. & Carpenter CL. Rho family GTPases bind to phosphoinositide kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1995; 270(30):17656-9. [PMID: 7629060]

- Auer KL. & Jacobson BS. Beta 1 integrins signal lipid second messengers required during cell adhesion. Mol. Biol. Cell 1995; 6(10):1305-13. [PMID: 8573788]

- Martel V., Racaud-Sultan C., Dupe S., Marie C., Paulhe F., Galmiche A., Block MR. & Albiges-Rizo C. Conformation, localization, and integrin binding of talin depend on its interaction with phosphoinositides. J. Biol. Chem. 2001; 276(24):21217-27. [PMID: 11279249]

- Campbell ID. & Ginsberg MH. The talin-tail interaction places integrin activation on FERM ground. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004; 29(8):429-35. [PMID: 15362227]

- Banno A., Goult BT., Lee H., Bate N., Critchley DR. & Ginsberg MH. Subcellular localization of talin is regulated by inter-domain interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287(17):13799-812. [PMID: 22351767]

- Rossier O., Octeau V., Sibarita JB., Leduc C., Tessier B., Nair D., Gatterdam V., Destaing O., Albigès-Rizo C., Tampé R., Cognet L., Choquet D., Lounis B. & Giannone G. Integrins β1 and β3 exhibit distinct dynamic nanoscale organizations inside focal adhesions. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012; 14(10):1057-67. [PMID: 23023225]

- Smith ML., Gourdon D., Little WC., Kubow KE., Eguiluz RA., Luna-Morris S. & Vogel V. Force-induced unfolding of fibronectin in the extracellular matrix of living cells. PLoS Biol. 2007; 5(10):e268. [PMID: 17914904]

- Jiang G., Giannone G., Critchley DR., Fukumoto E. & Sheetz MP. Two-piconewton slip bond between fibronectin and the cytoskeleton depends on talin. Nature 2003; 424(6946):334-7. [PMID: 12867986]

- Giannone G., Mège RM. & Thoumine O. Multi-level molecular clutches in motile cell processes. Trends Cell Biol. 2009; 19(9):475-86. [PMID: 19716305]

- Ivaska J. Unanchoring integrins in focal adhesions. Nat Cell Biol. 2012; 14(10):981-3. [PMID: 23033047]

- Critchley DR. & Gingras AR. Talin at a glance. J. Cell. Sci. 2008; 121(Pt 9):1345-7. [PMID: 18434644]

- Longley RL., Woods A., Fleetwood A., Cowling GJ., Gallagher JT. & Couchman JR. Control of morphology, cytoskeleton and migration by syndecan-4. J. Cell. Sci. 1999; 112 ( Pt 20):3421-31. [PMID: 10504291]

- Zimerman B., Volberg T. & Geiger B. Early molecular events in the assembly of the focal adhesion-stress fiber complex during fibroblast spreading. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 2004; 58(3):143-59. [PMID: 15146534]

- Morgan MR., Humphries MJ. & Bass MD. Synergistic control of cell adhesion by integrins and syndecans. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007; 8(12):957-69. [PMID: 17971838]

- Geiger B., Bershadsky A., Pankov R. & Yamada KM. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix–cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001; 2(11):793-805. [PMID: 11715046]

- Schvartzman M., Palma M., Sable J., Abramson J., Hu X., Sheetz MP. & Wind SJ. Nanolithographic control of the spatial organization of cellular adhesion receptors at the single-molecule level. Nano Lett. 2011; 11(3):1306-12. [PMID: 21319842]

- Coyer SR., Singh A., Dumbauld DW., Calderwood DA., Craig SW., Delamarche E. & García AJ. Nanopatterning Reveals an ECM Area Threshold for Focal Adhesion Assembly and Force Transmission that is regulated by Integrin Activation and Cytoskeleton Tension. J Cell Sci. 2012. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 22899715]

- Butler B., Gao C., Mersich AT. & Blystone SD. Purified integrin adhesion complexes exhibit actin-polymerization activity. Curr. Biol. 2006; 16(3):242-51. [PMID: 16461277]

- Yu CH., Law JB., Suryana M., Low HY. & Sheetz MP. Early integrin binding to Arg-Gly-Asp peptide activates actin polymerization and contractile movement that stimulates outward translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011; 108(51):20585-90. [PMID: 22139375]

- Roca-Cusachs P., Iskratsch T. & Sheetz MP. Finding the weakest link: exploring integrin-mediated mechanical molecular pathways. J. Cell. Sci. 2012; 125(Pt 13):3025-38. [PMID: 22797926]

- Ren XD., Kiosses WB., Sieg DJ., Otey CA., Schlaepfer DD. & Schwartz MA. Focal adhesion kinase suppresses Rho activity to promote focal adhesion turnover. J. Cell. Sci. 2000; 113 ( Pt 20):3673-8. [PMID: 11017882]

- Shi Q. & Boettiger D. A novel mode for integrin-mediated signaling: tethering is required for phosphorylation of FAK Y397. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003; 14(10):4306-15. [PMID: 12960434]

- Brown MC., Perrotta JA. & Turner CE. Identification of LIM3 as the principal determinant of paxillin focal adhesion localization and characterization of a novel motif on paxillin directing vinculin and focal adhesion kinase binding. J. Cell Biol. 1996; 135(4):1109-23. [PMID: 8922390]

- Mofrad MR., Golji J., Abdul Rahim NA. & Kamm RD. Force-induced unfolding of the focal adhesion targeting domain and the influence of paxillin binding. Mech Chem Biosyst 2004; 1(4):253-65. [PMID: 16783922]

- Arias-Salgado EG., Lizano S., Sarkar S., Brugge JS., Ginsberg MH. & Shattil SJ. Src kinase activation by direct interaction with the integrin beta cytoplasmic domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003; 100(23):13298-302. [PMID: 14593208]

- Reddy KB., Smith DM. & Plow EF. Analysis of Fyn function in hemostasis and alphaIIbbeta3-integrin signaling. J. Cell. Sci. 2008; 121(Pt 10):1641-8. [PMID: 18430780]

- Jiang G., Huang AH., Cai Y., Tanase M. & Sheetz MP. Rigidity sensing at the leading edge through alphavbeta3 integrins and RPTPalpha. Biophys. J. 2006; 90(5):1804-9. [PMID: 16339875]

- von Wichert G., Jiang G., Kostic A., De Vos K., Sap J. & Sheetz MP. RPTP-alpha acts as a transducer of mechanical force on alphav/beta3-integrin-cytoskeleton linkages. J. Cell Biol. 2003; 161(1):143-53. [PMID: 12682088]

- Ling K., Doughman RL., Firestone AJ., Bunce MW. & Anderson RA. Type I gamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase targets and regulates focal adhesions. Nature 2002; 420(6911):89-93. [PMID: 12422220]

- Kong X., Wang X., Misra S. & Qin J. Structural basis for the phosphorylation-regulated focal adhesion targeting of type Igamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase (PIPKIgamma) by talin. J. Mol. Biol. 2006; 359(1):47-54. [PMID: 16616931]

- Lawson C., Lim ST., Uryu S., Chen XL., Calderwood DA. & Schlaepfer DD. FAK promotes recruitment of talin to nascent adhesions to control cell motility. J. Cell Biol. 2012; 196(2):223-32. [PMID: 22270917]

- Margadant F., Chew LL., Hu X., Yu H., Bate N., Zhang X. & Sheetz M. Mechanotransduction in vivo by repeated talin stretch-relaxation events depends upon vinculin. PLoS Biol. 2011; 9(12):e1001223. [PMID: 22205879]

- Lee SE., Kamm RD. & Mofrad MR. Force-induced activation of talin and its possible role in focal adhesion mechanotransduction. J Biomech 2007; 40(9):2096-106. [PMID: 17544431]

- Ziegler WH., Gingras AR., Critchley DR. & Emsley J. Integrin connections to the cytoskeleton through talin and vinculin. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008; 36(Pt 2):235-9. [PMID: 18363566]

- del Rio A., Perez-Jimenez R., Liu R., Roca-Cusachs P., Fernandez JM. & Sheetz MP. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science 2009; 323(5914):638-41. [PMID: 19179532]

- Humphries JD., Wang P., Streuli C., Geiger B., Humphries MJ. & Ballestrem C. Vinculin controls focal adhesion formation by direct interactions with talin and actin. J. Cell Biol. 2007; 179(5):1043-57. [PMID: 18056416]

- Bos JL. Linking Rap to cell adhesion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005; 17(2):123-8. [PMID: 15780587]

- Brindle NP., Holt MR., Davies JE., Price CJ. & Critchley DR. The focal-adhesion vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) binds to the proline-rich domain in vinculin. Biochem. J. 1996; 318 ( Pt 3):753-7. [PMID: 8836115]

- Reinhard M., Halbrügge M., Scheer U., Wiegand C., Jockusch BM. & Walter U. The 46/50 kDa phosphoprotein VASP purified from human platelets is a novel protein associated with actin filaments and focal contacts. EMBO J. 1992; 11(6):2063-70. [PMID: 1318192]

- DeMali KA., Barlow CA. & Burridge K. Recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to vinculin: coupling membrane protrusion to matrix adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 2002; 159(5):881-91. [PMID: 12473693]

- Serrels B., Serrels A., Brunton VG., Holt M., McLean GW., Gray CH., Jones GE. & Frame MC. Focal adhesion kinase controls actin assembly via a FERM-mediated interaction with the Arp2/3 complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007; 9(9):1046-56. [PMID: 17721515]

- Le Clainche C. & Carlier MF. Regulation of actin assembly associated with protrusion and adhesion in cell migration. Physiol. Rev. 2008; 88(2):489-513. [PMID: 18391171]

- Zhang Y., Chen K., Tu Y., Velyvis A., Yang Y., Qin J. & Wu C. Assembly of the PINCH-ILK-CH-ILKBP complex precedes and is essential for localization of each component to cell-matrix adhesion sites. J. Cell. Sci. 2002; 115(Pt 24):4777-86. [PMID: 12432066]

- Li F., Zhang Y. & Wu C. Integrin-linked kinase is localized to cell-matrix focal adhesions but not cell-cell adhesion sites and the focal adhesion localization of integrin-linked kinase is regulated by the PINCH-binding ANK repeats. J. Cell. Sci. 1999; 112 ( Pt 24):4589-99. [PMID: 10574708]

- Hannigan GE., Leung-Hagesteijn C., Fitz-Gibbon L., Coppolino MG., Radeva G., Filmus J., Bell JC. & Dedhar S. Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new beta 1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature 1996; 379(6560):91-6. [PMID: 8538749]

- Pasquet JM., Noury M. & Nurden AT. Evidence that the platelet integrin alphaIIb beta3 is regulated by the integrin-linked kinase, ILK, in a PI3-kinase dependent pathway. Thromb. Haemost. 2002; 88(1):115-22. [PMID: 12152651]

- Tucker KL., Sage T., Stevens JM., Jordan PA., Jones S., Barrett NE., St-Arnaud R., Frampton J., Dedhar S. & Gibbins JM. A dual role for integrin-linked kinase in platelets: regulating integrin function and alpha-granule secretion. Blood 2008; 112(12):4523-31. [PMID: 18772455]

- Legate KR., Montañez E., Kudlacek O. & Fässler R. ILK, PINCH and parvin: the tIPP of integrin signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006; 7(1):20-31. [PMID: 16493410]