Axon Guidance

Content

What is axon guidance and the growth cone?[Edit]

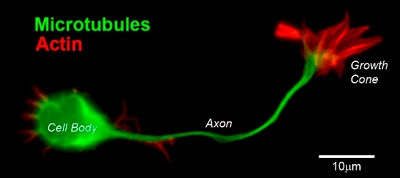

Axon guidance is an important step in neural development. It allows growing axons to reach specific destinations and ultimately form the complex neuronal networks throughout the body. Although many aspects of this mechanism remains unclear, it is well established that a dynamic and highly motile actin-based structure found at the growing end of a developing axon, known as a growth cone, facilitates this process.

The Growth Cone

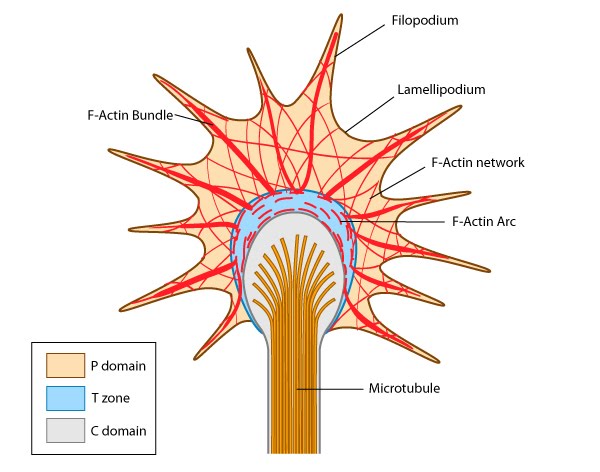

Growth cones facilitate axon growth and guidance by bundling and extending actin filaments into structures known as filopodia and microspikes. Binding of filopodia and adhesion receptors to particular extracellular matrix (ECM) components or ligands is translated into actin filament assembly, cytoskeleton remodeling and force-driven motility. These events culminate in the growth of the neuron towards its target. Growth cones contain a number of cytoskeletal components that are organized into three regions; the peripheral (P) domain, the transitional (T) domain and the central (C) domain [1]:

The P domain is primarily composed of unipolar actin filament bundles embedded in a less polar actin network. It contains dynamic lamellipodia and filopodia. Microtubules are also transiently found within this domain.

The C domain is located in the center of the growth cone nearest the axon. It is primarily composed of microtubules and contains numerous organelles and vesicles.

The T domain is a thin interface between the C and P domains.

A number of cytoskeletal-associated proteins are present in growth cones that anchor actin filaments and microtubules to each other (e.g. myosin II [2]), to the membrane (e.g. talin [3]) and to other cytoskeletal components. Molecular motors present in growth cones produce the forces needed for growth cone migration (e.g. myosin II [4]) and vesicle transport in and out of the growth cone (e.g. KIF4 (kinesin superfamily protein member 4) [5]).

Guidance cues can be attractive or repulsive[Edit]

Guidance cues come in many different forms, from diffusible extracellular proteins and lipid factors, to extracellular matrix proteins and/or carbohydrates located on the cell substrate. They may also originate from membrane of adjacent cells.

* Guidance cues are secreted or expressed at the right time and place.

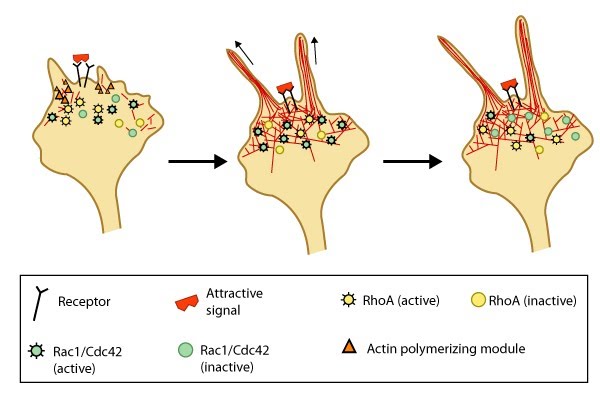

Figure 3. Attractive cues promote filopodia formation: In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion is induced when an attractive cue binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently activates Cdc42/Rac1 GTPase and subsequent recruitment of adhesion molecules and components of the actin polymerizing module (e.g. Arp2/3 complex and formins such as mDia2)which together promote filopodia protrusion. Rac1/Cdc42 activity is then locally reduced in the filopodium, which allows RhoA and its effector, ROCK, to become activated; ROCK is involved with subsequent stabilization and maturation of adhesions, which supports migration in the direction of the attractive signal.

Figure 3. Attractive cues promote filopodia formation: In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion is induced when an attractive cue binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently activates Cdc42/Rac1 GTPase and subsequent recruitment of adhesion molecules and components of the actin polymerizing module (e.g. Arp2/3 complex and formins such as mDia2)which together promote filopodia protrusion. Rac1/Cdc42 activity is then locally reduced in the filopodium, which allows RhoA and its effector, ROCK, to become activated; ROCK is involved with subsequent stabilization and maturation of adhesions, which supports migration in the direction of the attractive signal.

To be considered a guidance cue, the molecule or protein must meet the following criteria:

* Guidance cues are secreted or expressed at the right time and place.

* The absence of the factor, or mutations in their receptors, lead to growth cone navigational errors.

* The secretion or expression of the guidance cue is sufficient to cause attraction/repulsion of the filopodium/growth cone (reviewed in [6]).

Figure 3. Attractive cues promote filopodia formation: In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion is induced when an attractive cue binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently activates Cdc42/Rac1 GTPase and subsequent recruitment of adhesion molecules and components of the actin polymerizing module (e.g. Arp2/3 complex and formins such as mDia2)which together promote filopodia protrusion. Rac1/Cdc42 activity is then locally reduced in the filopodium, which allows RhoA and its effector, ROCK, to become activated; ROCK is involved with subsequent stabilization and maturation of adhesions, which supports migration in the direction of the attractive signal.

Figure 3. Attractive cues promote filopodia formation: In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion is induced when an attractive cue binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently activates Cdc42/Rac1 GTPase and subsequent recruitment of adhesion molecules and components of the actin polymerizing module (e.g. Arp2/3 complex and formins such as mDia2)which together promote filopodia protrusion. Rac1/Cdc42 activity is then locally reduced in the filopodium, which allows RhoA and its effector, ROCK, to become activated; ROCK is involved with subsequent stabilization and maturation of adhesions, which supports migration in the direction of the attractive signal.In most cases, there are multiple receptors for each guidance cue; however, it is widely known that the final outcome resulting from guidance cue-induced events is dependent upon the cell type, the duration the signal is ‘on’, the state of the cell (e.g. differentiation state, cell cycle stage, etc), and the concentration of the guidance cue.

The guidance signals for neuronal growth cone movement are among the most widely studied [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] (reviewed in [13, 14]). The generation of a signal concentration gradient allows cells to use a directional sensing program to generate “front”-specific responses at the region where the signal is the highest and “rear” specific responses where the signal is the lowest. The activation of localized signal transduction events results in positional cues that promote the relocalization of certain proteins to the front or back of the cell. Subsequent cytoskeletal restructuring redirects the migration of the growth cone (reviewed in [6, 15,16]). The final response to many guidance signals can be affected by the level of both intra- and extracellular calcium [17, 18, 19].

The guidance signals for neuronal growth cone movement are among the most widely studied [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] (reviewed in [13, 14]). The generation of a signal concentration gradient allows cells to use a directional sensing program to generate “front”-specific responses at the region where the signal is the highest and “rear” specific responses where the signal is the lowest. The activation of localized signal transduction events results in positional cues that promote the relocalization of certain proteins to the front or back of the cell. Subsequent cytoskeletal restructuring redirects the migration of the growth cone (reviewed in [6, 15,16]). The final response to many guidance signals can be affected by the level of both intra- and extracellular calcium [17, 18, 19].

Most known attractive signals act as chemoattractants, often generating the formation of adhesion molecules within the growth cone to promote selective extension of the filopodia towards the cue, whilst ensuring the formation of filopodia or lamellipodia is decreased in other directions. This occurs through a decreased retrograde actin flow in the direction of the contact [20, 21]. Such attractive cues are propagated by the Rho family of GTPases (e.g. Rac1, Cdc42 and RhoA) following ligand-induced receptor binding to the cytoskeleton (reviewed in[1]). Attractive cues such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) activate Cdc42 and Rac [22], and Rac1 activity in turn influences the initial formation of integrin-dependent adhesions in the growth cone. In this case, further adhesion stabilization and continued migration requires proper coordination between Rac1 and RhoA GTPase activity [23, 24]. Local signals may also redirect the signal through other recruited components [9, 22, 25, 26].

Repulsive cues

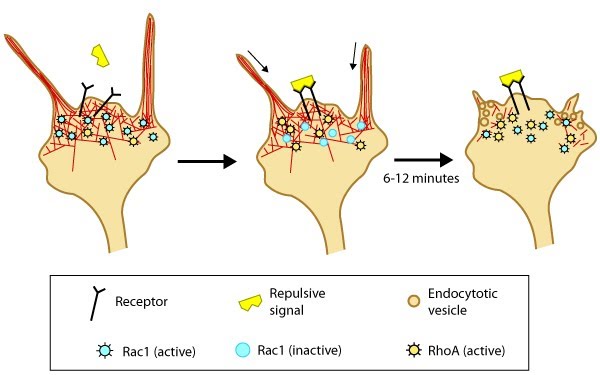

In the case of repulsive signals, the actin assembly module is suggested to rapidly terminate growth in synchrony with the release of linkages between the cytoskeleton and the membrane [27, 28]. Growth cone collapse is a key example of how neural cells respond to repulsive cues by altering actin filament dynamics. Growth cone collapse involves numerous signaling pathways including Rho GTPases [29], ADF [30], and kinases [31, 32].

Figure 4. Model of filopodia collapse: In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion stops when a repulsive signal binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently inactivates Rac1 GTPase and prevents it from promoting actin assembly. Resumption of Rac1 activity coincides with filopodia collapse and is required for endocytosis of the collapsing plasma membrane and reorganization of F-actin [33]. RhoA and its effector, ROCK, are activated downstream of repulsive cues [34, 33, 35] and their activity has been implicated in reducing actin polymerization following treatment with repulsive signals [36].A model for filopodia collapse in growth cones was created using the repulsive signal, semaphorin IIIA (SemaIIIA; collapsin-1). Another example is reelin, a large secretory protein that inhibits filopodia formation through a pathway involving Fyn or Src kinase-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation of mDab1 (mouse Disabled homologue 1) [37]. Phosphorylation of mDab1 reduces the activation of N-WASP and Arp2/3-dependent actin polymerization [38].

Figure 4. Model of filopodia collapse: In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion stops when a repulsive signal binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently inactivates Rac1 GTPase and prevents it from promoting actin assembly. Resumption of Rac1 activity coincides with filopodia collapse and is required for endocytosis of the collapsing plasma membrane and reorganization of F-actin [33]. RhoA and its effector, ROCK, are activated downstream of repulsive cues [34, 33, 35] and their activity has been implicated in reducing actin polymerization following treatment with repulsive signals [36].A model for filopodia collapse in growth cones was created using the repulsive signal, semaphorin IIIA (SemaIIIA; collapsin-1). Another example is reelin, a large secretory protein that inhibits filopodia formation through a pathway involving Fyn or Src kinase-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation of mDab1 (mouse Disabled homologue 1) [37]. Phosphorylation of mDab1 reduces the activation of N-WASP and Arp2/3-dependent actin polymerization [38].

Figure 4. Model of filopodia collapse: In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion stops when a repulsive signal binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently inactivates Rac1 GTPase and prevents it from promoting actin assembly. Resumption of Rac1 activity coincides with filopodia collapse and is required for endocytosis of the collapsing plasma membrane and reorganization of F-actin [33]. RhoA and its effector, ROCK, are activated downstream of repulsive cues [34, 33, 35] and their activity has been implicated in reducing actin polymerization following treatment with repulsive signals [36].

Figure 4. Model of filopodia collapse: In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion stops when a repulsive signal binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently inactivates Rac1 GTPase and prevents it from promoting actin assembly. Resumption of Rac1 activity coincides with filopodia collapse and is required for endocytosis of the collapsing plasma membrane and reorganization of F-actin [33]. RhoA and its effector, ROCK, are activated downstream of repulsive cues [34, 33, 35] and their activity has been implicated in reducing actin polymerization following treatment with repulsive signals [36].Signal integration

It is not always clear whether a guidance signal provides information for both directional and temporal movement. However, they can be integrated temporally and/or spatially:Temporal integration:

Lamellipodial and filopodial protrusions at the leading edge of migrating cells and neural growth cones are exposed to a number of guidance cues simultaneously and the proper integrated response is necessary for proper cell/growth cone guidance and maintenance. In certain cases, prior exposure to one signal initiates cytoplasmic events that prevent or ‘desensitize’ the cell to subsequent guidance cues (reviewed in [39, 40]).Cyclic nucleotides can regulate growth cone behaviors by converting repulsive signals to attractive signals through the activation of cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cGMP) and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) signaling pathways, respectively (reviewed in [39]). For example, the small molecule netrin, induces attractive or repulsive signals depending on the type of receptors expressed and on the intracellular level of cAMP [18].

Other guidance cues function as attractants for one navigational event and a repellent for another (reviewed in [41]); similarly, the signal molecules that are activated by these guidance cues frequently antagonize each others’ activity, emphasizing the importance of proper coordination between these signaling components [23, 24]. Not surprisingly, mutation(s) in the signaling pathways that are used by guidance cues frequently results in aberrant navigation (reviewed in[6]).

Other guidance cues function as attractants for one navigational event and a repellent for another (reviewed in [41]); similarly, the signal molecules that are activated by these guidance cues frequently antagonize each others’ activity, emphasizing the importance of proper coordination between these signaling components [23, 24]. Not surprisingly, mutation(s) in the signaling pathways that are used by guidance cues frequently results in aberrant navigation (reviewed in[6]).

Examples of Guidance Cues; Neurotrophins, Collapsin and Ephrins[Edit]

Neurotrophins

Stimulating filopodia formation A secreted guidance cue which stimulates filopodia formation in growth cones. Two examples of secreted neurotrophins, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF), mediate retinal ganglion cell axon filopodia [42] and sprouting of axonal filopodia, respectively [43]. Neurotrophins bind Trk receptors and the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) to regulate both filopodia assembly and length [20]. Neurotrophins stimulate filopodial assembly by influencing actin-dependent nucleation, polymerization, and motility through PI-3 kinase-dependent signal transduction pathways [44, 45].

Collapsin-1

Inducing filopodia collapse in chick and its mammalian orthologue, semaphorin III (SemaIII) are a few of the most extensively studied proteins that cause repulsion or collapse of growth cones in particular neuronal classes. Members of this group are secreted and transmembrane proteins; they bind to neurophilin receptors to stimulate repulsion (reviewed in [46]). SemaIIIA causes termination of protrusive activity and growth cone collapse [47] through activation of Rac1 [48] and decreased phosphorylation of the ezrin–radixin–moesin (ERM)family of F-actin binding proteins [49]. Phosphorylation of ERM proteins activates the F-actin binding domain and regulates filopodia assembly/protrusion by linking filopodial membranes with F-actin (reviewed in [50]). Inactivation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signal pathway by SemaIIIA may also be linked to reduced ERM protein activity and growth cone collapse [49].Ephrins

Ephrins are contact-dependent guidance cues that induce both attractive and repulsive signals [51]. These signals are transduced via ephrin binding to Eph receptors that belong to the receptor tyrosine kinase family. Binding of membrane-bound ephrins to Eph receptors induces receptor clustering, activation and subsequent signal transduction (forward signaling). The reverse is also true, with Eph receptors binding ephrins and inducing clustering of this ligand and signal transduction (reverse signaling) (reviewed in [52]). Eph-ephrin signaling is therefore bidirectional, with both components able to act as receptor or ligand. Soluble ephrins are also able to bind Eph receptors, but this does not promote signal transduction, unless the ephrins are artificially membrane-bound [53].Membrane-bound ephrins can be divided into two main classes, determined by sequence homology, which reflect the means by which they attach to the membrane. ‘Ephrin A’s that bind to the membrane via glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors and ‘ephrin B’s that traverse the membrane via their transmembrane domain and contain a short cytoplasmic tail [54].

In general ephrin As bind Eph A receptors and ephrin Bs bind Eph B receptors [Gale] and in both instances facilitate bidirectional signaling, though reverse signaling in ephrin A-Eph A complexes is poorly understood. Both ephrin As and Bs contain a well conserved extracellular domain that binds Eph receptors. Ephrin Bs additionally contain conserved tyrosine phosphorylation sites and a PDZ domain in their cytoplasmic tails that facilitate intracellular signaling (reviewed in [52]).

The primary role of ephrin-Eph receptor signaling is to regulate cellular patterning e.g. guiding neuronal growth cones to the appropriate target. A significant body of work has elucidated the role of ephrins in neural development (as reviewed in [5]). For example; Ephrin Bs are of particular importance in patterning of the hindbrain – a distinctly segmented structure within the brain. Ephrins Bs and their cognate Eph receptors are expressed in complementary domains, such that mixing of neuronal cells is prevented by repulsive cues resulting from the interaction of ephrin Bs and Eph receptors at the interfaces between two adjacent domains [6].

Other processes highly dependent on cell-cell contacts that involve ephrins include the maturation of of thymocytes into T-cells of the immune system, the release of insulin from pancreatic beta cells, osteoblast differentiation and segregation of dividing and differentiated cells of the intestinal epithelium. Under pathological conditions, the dysregulation of Eph-ephrin expression has been implicated in cancer and in the development of tumor vasculature (tumour angiogenesis) (as reviewed in [7]).