Steps in Formation 1. Initiation 2. Extension 3. Lateral movement and Stasis 4. Adherence 5. Pulling 6. Retraction and Collapse Functional Modules

| Filopodia

|

| System | Maximum Rate | References |

| Mouse cortical neurons; primary mesenchyme cells | 400 nm/s | [4, 5] |

| NG108 | 15 nm/s | [6] |

| Mouse macrophage | 600 nm/s | [7] |

| Chick DRG neurons | 200 nm/s | [8] |

Rapid collapse produces a large number of filopodial strands tightly connected to the substrate by long tethers. F-actin bundles [9] and monomeric actin [2] disappear from collapsing filopodia without a compensatory rise in F-actin at the growth cone center; this indicates a net loss of actin rather than a rearward translocation. Furthermore, active nucleation and protrusion of filopodia is still found in discrete areas of collapsing growth cones, which argues against sequesterization or modification of actin as the mechanism responsible for the loss of F-actin during the collapse [2].

A number of factors regulate collapse and retraction. For example, capping proteins promote filopodial retraction by shielding the barbed end of filaments from further assembly and elongation [10]. Inhibition of F-actin polymerization and protrusion during collapse are mediated by RhoA kinase activity [11]. Collapse may result from the exposure of a “naive” growth cone to a high concentration of a repellent followed by an overactive response [12]. The repulsive component appears to shut down the growth program and is, therefore, dominant over the growth-stimulating effects of adhesion molecules. In addition, the repellent also interferes with mechanisms that would normally result in filopodial retraction [1].

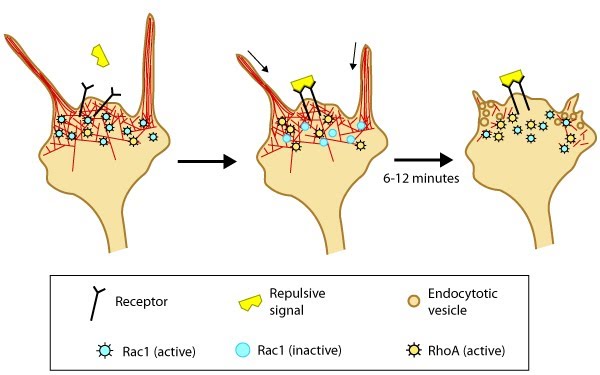

Figure: Model of filopodia collapse. In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion stops when a repulsive signal binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently inactivates Rac1 GTPase and prevents it from promoting actin assembly. Resumption of Rac1 activity coincides with filopodia collapse and is required for endocytosis of the collapsing plasma membrane and reorganization of F-actin [3]. RhoA activity has also been implicated in reducing actin polymerization following treatment with repulsive signals [11].

Figure: Model of filopodia collapse. In neuronal growth cones, filopodia protrusion stops when a repulsive signal binds to its receptor on the cell surface. Receptor-binding transiently inactivates Rac1 GTPase and prevents it from promoting actin assembly. Resumption of Rac1 activity coincides with filopodia collapse and is required for endocytosis of the collapsing plasma membrane and reorganization of F-actin [3]. RhoA activity has also been implicated in reducing actin polymerization following treatment with repulsive signals [11].

Growth Cone Collapse

Growth cone collapse is a complex phenomenon involving numerous signal pathways including Rho-GTPases [13], ADF [14], and kinases [15, 16]. A model for filopodia collapse in growth cones was created using the guidance signal, semaphorin IIIA (SemaIIIA; collapsin-1). SemaIIIA causes termination of protrusive activity and growth cone collapse [17] through decreased phosphorylation of the ezrin–radixin–moesin (ERM) family of F-actin binding proteins [18]. Phosphorylation of ERM proteins activates the F-actin binding domain and regulates filopodia assembly/protrusion by linking filopodial membranes with F-actin (reviewed in [19]). Inactivation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signal pathway by SemaIIIA may also be linked to reduced ERM protein activity and growth cone collapse [18].References

- Bastmeyer M. & Stuermer CA. Behavior of fish retinal growth cones encountering chick caudal tectal membranes: a time-lapse study on growth cone collapse. J. Neurobiol. 1993; 24(1):37-50. [PMID: 8419523]

- Fan J., Mansfield SG., Redmond T., Gordon-Weeks PR. & Raper JA. The organization of F-actin and microtubules in growth cones exposed to a brain-derived collapsing factor. J. Cell Biol. 1993; 121(4):867-78. [PMID: 8491778]

- Jurney WM., Gallo G., Letourneau PC. & McLoon SC. Rac1-mediated endocytosis during ephrin-A2- and semaphorin 3A-induced growth cone collapse. J. Neurosci. 2002; 22(14):6019-28. [PMID: 12122063]

- Sheetz MP., Wayne DB. & Pearlman AL. Extension of filopodia by motor-dependent actin assembly. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 1992; 22(3):160-9. [PMID: 1423662]

- Miller J., Fraser SE. & McClay D. Dynamics of thin filopodia during sea urchin gastrulation. Development 1995; 121(8):2501-11. [PMID: 7671814]

- Mallavarapu A. & Mitchison T. Regulated actin cytoskeleton assembly at filopodium tips controls their extension and retraction. J. Cell Biol. 1999; 146(5):1097-106. [PMID: 10477762]

- Kress H., Stelzer EH., Holzer D., Buss F., Griffiths G. & Rohrbach A. Filopodia act as phagocytic tentacles and pull with discrete steps and a load-dependent velocity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007; 104(28):11633-8. [PMID: 17620618]

- Costantino S., Kent CB., Godin AG., Kennedy TE., Wiseman PW. & Fournier AE. Semi-automated quantification of filopodial dynamics. J. Neurosci. Methods 2008; 171(1):165-73. [PMID: 18394712]

- Zhou FQ. & Cohan CS. Growth cone collapse through coincident loss of actin bundles and leading edge actin without actin depolymerization. J. Cell Biol. 2001; 153(5):1071-84. [PMID: 11381091]

- Lin CH., Espreafico EM., Mooseker MS. & Forscher P. Myosin drives retrograde F-actin flow in neuronal growth cones. Neuron 1996; 16(4):769-82. [PMID: 8607995]

- Gallo G. RhoA-kinase coordinates F-actin organization and myosin II activity during semaphorin-3A-induced axon retraction. J. Cell. Sci. 2006; 119(Pt 16):3413-23. [PMID: 16899819]

- Walter J., Allsopp TE. & Bonhoeffer F. A common denominator of growth cone guidance and collapse? Trends Neurosci. 1990; 13(11):447-52. [PMID: 1701577]

- Liu BP. & Strittmatter SM. Semaphorin-mediated axonal guidance via Rho-related G proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001; 13(5):619-26. [PMID: 11544032]

- Aizawa H., Wakatsuki S., Ishii A., Moriyama K., Sasaki Y., Ohashi K., Sekine-Aizawa Y., Sehara-Fujisawa A., Mizuno K., Goshima Y. & Yahara I. Phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase is necessary for semaphorin 3A-induced growth cone collapse. Nat. Neurosci. 2001; 4(4):367-73. [PMID: 11276226]

- Sasaki Y., Cheng C., Uchida Y., Nakajima O., Ohshima T., Yagi T., Taniguchi M., Nakayama T., Kishida R., Kudo Y., Ohno S., Nakamura F. & Goshima Y. Fyn and Cdk5 mediate semaphorin-3A signaling, which is involved in regulation of dendrite orientation in cerebral cortex. Neuron 2002; 35(5):907-20. [PMID: 12372285]

- Eickholt BJ., Walsh FS. & Doherty P. An inactive pool of GSK-3 at the leading edge of growth cones is implicated in Semaphorin 3A signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2002; 157(2):211-7. [PMID: 11956225]

- Luo Y., Raible D. & Raper JA. Collapsin: a protein in brain that induces the collapse and paralysis of neuronal growth cones. Cell 1993; 75(2):217-27. [PMID: 8402908]

- Gallo G. Semaphorin 3A inhibits ERM protein phosphorylation in growth cone filopodia through inactivation of PI3K. Dev Neurobiol 2008; 68(7):926-33. [PMID: 18327764]

- Bretscher A., Edwards K. & Fehon RG. ERM proteins and merlin: integrators at the cell cortex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002; 3(8):586-99. [PMID: 12154370]