Actin Filament Bundle Assembly

Content

Introduction to Actin Bundle Assembly[Edit]

Crosslinking of actin filaments is a critical step in cell motility and is a fundamental process in filopodia protrusion and lamellipodia formation.

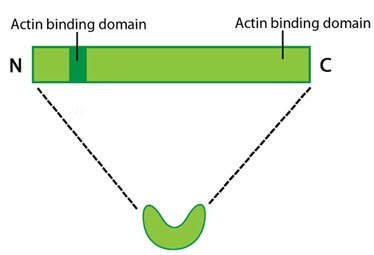

Figure 1. Types of actin filament crosslinking proteins: Smaller cross-linking proteins that are more globular (e.g. fascin) or have more than one actin binding site (e.g. fimbrin, α-actinin dimers) primarily form actin bundles. Larger crosslinking proteins (e.g. spectrin, filamin, dystrophin) create more space between actin filaments and they generally form actin networks. Other actin crosslinking proteins not shown here include: scruin, dematin, and villin.In filopodia, crosslinking of actin filaments provides the rigidity needed to overcome the compressive force of the plasma membrane, which individual actin filaments otherwise lack [1, 2]. Filopodia in nerve growth cones contain tightly packed bundles of actin filaments that usually contain more than 15 parallel filaments. These are likely to be oriented with their barbed ends towards the tip [3]. Mechanically, a crosslinked filopodial bundle functions as an effective elastic rod. Bundle stiffness increases with the number of bundled filaments and so contributes to the overall filopodium length [1].

Figure 1. Types of actin filament crosslinking proteins: Smaller cross-linking proteins that are more globular (e.g. fascin) or have more than one actin binding site (e.g. fimbrin, α-actinin dimers) primarily form actin bundles. Larger crosslinking proteins (e.g. spectrin, filamin, dystrophin) create more space between actin filaments and they generally form actin networks. Other actin crosslinking proteins not shown here include: scruin, dematin, and villin.In filopodia, crosslinking of actin filaments provides the rigidity needed to overcome the compressive force of the plasma membrane, which individual actin filaments otherwise lack [1, 2]. Filopodia in nerve growth cones contain tightly packed bundles of actin filaments that usually contain more than 15 parallel filaments. These are likely to be oriented with their barbed ends towards the tip [3]. Mechanically, a crosslinked filopodial bundle functions as an effective elastic rod. Bundle stiffness increases with the number of bundled filaments and so contributes to the overall filopodium length [1].

In lamellipodia, crosslinking also strengthens the actin filaments, however in this case the filaments form a branched network, which is connected at certain points to membrane bound proteins and focal adhesions (as depicted in Fig 1). Crosslinking also increases the ATPase activity of myosins and increases the tension on actin filaments [4].

A number of proteins including fascin, filamin, α-actinin, and members of the I-BAR family of proteins serve as functional modules in actin crosslinking (see figure below). In each case these proteins bind to two actin filaments, and in some cases, additional regulatory proteins. Despite considerable redundancy between F-actin crosslinking proteins, their specific subcellular localization suggests that each of these proteins may play a unique role in coordinating the organization of actin (reviewed in [5]).

Figure 1. Types of actin filament crosslinking proteins: Smaller cross-linking proteins that are more globular (e.g. fascin) or have more than one actin binding site (e.g. fimbrin, α-actinin dimers) primarily form actin bundles. Larger crosslinking proteins (e.g. spectrin, filamin, dystrophin) create more space between actin filaments and they generally form actin networks. Other actin crosslinking proteins not shown here include: scruin, dematin, and villin.

Figure 1. Types of actin filament crosslinking proteins: Smaller cross-linking proteins that are more globular (e.g. fascin) or have more than one actin binding site (e.g. fimbrin, α-actinin dimers) primarily form actin bundles. Larger crosslinking proteins (e.g. spectrin, filamin, dystrophin) create more space between actin filaments and they generally form actin networks. Other actin crosslinking proteins not shown here include: scruin, dematin, and villin.In lamellipodia, crosslinking also strengthens the actin filaments, however in this case the filaments form a branched network, which is connected at certain points to membrane bound proteins and focal adhesions (as depicted in Fig 1). Crosslinking also increases the ATPase activity of myosins and increases the tension on actin filaments [4].

A number of proteins including fascin, filamin, α-actinin, and members of the I-BAR family of proteins serve as functional modules in actin crosslinking (see figure below). In each case these proteins bind to two actin filaments, and in some cases, additional regulatory proteins. Despite considerable redundancy between F-actin crosslinking proteins, their specific subcellular localization suggests that each of these proteins may play a unique role in coordinating the organization of actin (reviewed in [5]).

Fascin[Edit]

Fascin is the major actin crosslinking protein found in a wide range of filopodia [6, 7, 8]. This protein has been shown to work in concert with other cross linkers such as α-actinin to produce filopodia, although fascin itself is sufficient to form filopodia-like bundles in a reconstitution system [9]. Moreover, fascin and α-actinin are observed to co-localize at the base of filopodia, where together they can produce a mechanical response of greater magnitude than when acting alone [10]. Cells harboring defective fascin create less filopodia and their mechanical properties are drastically compromised [11]. In lamellipodia-like structures, fascin is suggested to organize the actin cytoskeleton at the leading edge to promote cell motility[12].

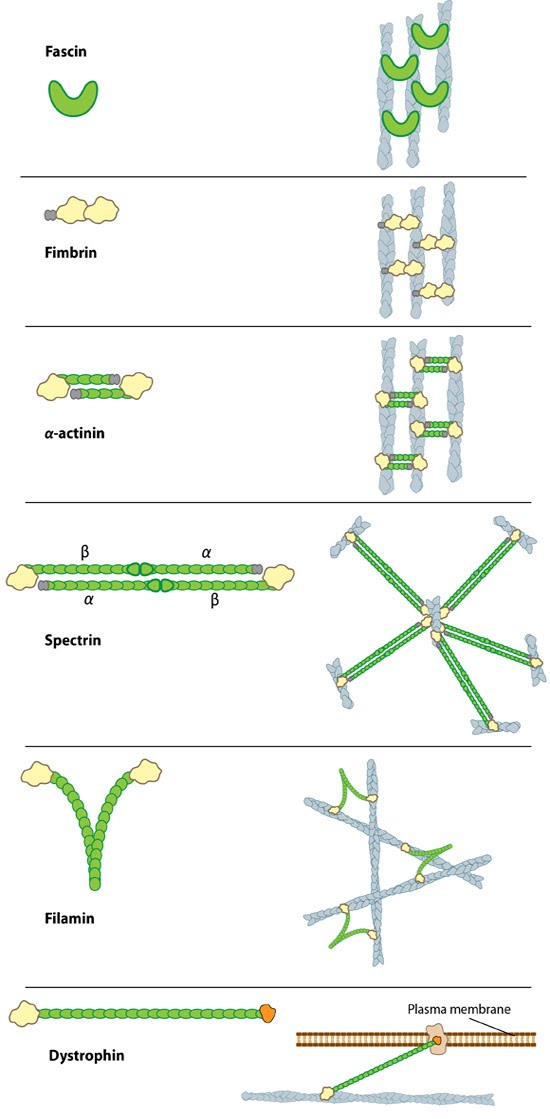

Protein structure A 55kDa globular protein that is a component of the crosslinking actin filaments functional module. Fascin organizes F-actin into tightly packed parallel bundles approximately 8nm apart. It also promotes side-branching of actin filaments and can crosslink actin filaments without forming bundles [13]. Metazoans contain three fascin forms (e.g. fascin-1, -2, and -3) encoded by three separate genes while invertebrates contain a single form of fascin (reviewed in [14]). Fascin contains two actin-binding domains (ABD), one located at each end of the protein (see figure below) [15, 16, 17]. Fascin binds to actin filaments with a stoichiometry in a range of one molecule of fascin to 2-3 molecules of actin (in brain tissue) [6] or 1:4 (in vitro) [7].

Fascin is found in the most distal regions of filopodia and lamellipodia and the cellular distribution of fascin within actin bundles (e.g. microspikes and stress fibers [18]) appears to vary depending upon the extracellular substrate [19, 20, 21]; however, specific details about how this distribution and assembly on the actin filaments is regulated remains largely unknown [11].

Localization and function

A steady pool of F-actin monomers or loosely linked F-actin promotes efficient polymerization and bundling of actin-filaments by fascin (reviewed in [14]). Fascin phosphorylation at the amino-terminal actin binding site by protein kinase Cα (PKCα) inhibits its ability to bind actin (at both sites) and to form bundles [15, 16]. Although fascin undergoes frequent cycles of association and dissociation rather than binding to actin filaments stably, this process is independent of the phosphorylation state [11]. The rate at which fascin dissociates from actin is slow and appears to contribute to the reduced movement of actin filaments and bundles i.e. increased stiffness of the actin network [13].Fascin is found in the most distal regions of filopodia and lamellipodia and the cellular distribution of fascin within actin bundles (e.g. microspikes and stress fibers [18]) appears to vary depending upon the extracellular substrate [19, 20, 21]; however, specific details about how this distribution and assembly on the actin filaments is regulated remains largely unknown [11].

Filamin[Edit]

The filamin family of proteins bind to both actin and a number of signaling molecules including Rho GTPases. Evidence for this was shown with the loss of Filamin-A in M2 Melanoma cells, which prevented RalA- and Cdc42-mediated filopodia formation [22]. Filamin A is necessary for the successful production of lamellipodia [23, 24], specifically due to its F-actin crosslinking activity [24]. Following recruitment to the membrane at the leading edge of a lamellipodium, it crosslinks newly polymerized actin filaments to enhance lamellipodium formation [24].

Figure 3. Filamin: This schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of filamin [25] and provides examples for how the filamin dimer is represented in figures throughout this resource. The ABD is at the amino (N)-terminus in contrast to the opposite end (the carboxy [C]-terminus), which contains a significant number of protein-protein interaction domains (reviewed in [26]).Filamin is an actin-binding protein that was first recognized (and named) for its filamentous colocalization with actin stress fibers [27]. Filamin molecules are naturally found in cells as elongated, V-shaped dimers (i.e. two linked filamin molecules) [28] that contain several immunoglobulin-like domains for protein interactions, amino-terminal actin-binding domains (ABD) composed of two calponin homology (CH) domains, and a carboxy-terminal dimerization domain (see Figure below) [29] (reviewed in [22]).

Figure 3. Filamin: This schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of filamin [25] and provides examples for how the filamin dimer is represented in figures throughout this resource. The ABD is at the amino (N)-terminus in contrast to the opposite end (the carboxy [C]-terminus), which contains a significant number of protein-protein interaction domains (reviewed in [26]).Filamin is an actin-binding protein that was first recognized (and named) for its filamentous colocalization with actin stress fibers [27]. Filamin molecules are naturally found in cells as elongated, V-shaped dimers (i.e. two linked filamin molecules) [28] that contain several immunoglobulin-like domains for protein interactions, amino-terminal actin-binding domains (ABD) composed of two calponin homology (CH) domains, and a carboxy-terminal dimerization domain (see Figure below) [29] (reviewed in [22]).

Filamin binds all actin isoforms (e.g. F-actin, G-actin) and its structural organization allows it to form a flexible bridge between two actin filaments at various angles, thereby imparting the actin network with loose or gel-like qualities [30]. Filamin also simultaneously interacts with and influences the activity of a number of other diverse proteins (e.g. transmembrane receptors, cell adhesion molecules, signaling molecules) through its immunoglobulin-like domains (reviewed in [22, 31, 26]). In some instances, the majority of these repeats are utilized for protein-protein interactions (e.g. beta-integrin binding [32]).

Figure 3. Filamin: This schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of filamin [25] and provides examples for how the filamin dimer is represented in figures throughout this resource. The ABD is at the amino (N)-terminus in contrast to the opposite end (the carboxy [C]-terminus), which contains a significant number of protein-protein interaction domains (reviewed in [26]).

Figure 3. Filamin: This schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of filamin [25] and provides examples for how the filamin dimer is represented in figures throughout this resource. The ABD is at the amino (N)-terminus in contrast to the opposite end (the carboxy [C]-terminus), which contains a significant number of protein-protein interaction domains (reviewed in [26]).Filamin binds all actin isoforms (e.g. F-actin, G-actin) and its structural organization allows it to form a flexible bridge between two actin filaments at various angles, thereby imparting the actin network with loose or gel-like qualities [30]. Filamin also simultaneously interacts with and influences the activity of a number of other diverse proteins (e.g. transmembrane receptors, cell adhesion molecules, signaling molecules) through its immunoglobulin-like domains (reviewed in [22, 31, 26]). In some instances, the majority of these repeats are utilized for protein-protein interactions (e.g. beta-integrin binding [32]).

Filamin Localization and Function

Filamin forms a vital scaffolding adaptor and regulatory component that contributes to the mechanical stability of cells by linking the internal actin network with membrane receptors and mechanosensitive components. This function correlates with its distribution in cultured cells along actin stress fibers, within cortical actin networks and sometimes at membrane ruffles [33, 34].

Numerous filamin isoforms exist in metazoan cells (reviewed in [22, 31]) and in some cases their cellular distribution suggests that certain isoforms may have specialized roles within the cell [35]. In muscle cells, filamin is locally concentrated at specific points called Z-lines, but in non-muscle cells filamin generally remains distributed throughout larger actin-based structures such as the lamellipodium, cortical actin, stress fibers and at sites of adhesion [reviewed in (4)].

Filamin not only binds to membrane receptors and to the Rho family of GTPases to influence actin organization (reviewed in [31]), but can itself directly transduce mechanical signals (e.g. stress) to regulate the cell stiffness [36] and possibly alter cellular adhesion [37]. Filamin can be phosphorylated by numerous kinases including cAMP-dependent protein kinase (i.e. protein kinase A) [38, 39] and protein kinase C [40]. Filamin phosphorylation not only regulates its interaction with other proteins and affects its ability to cross-link actin, but also regulates its stability and proteolysis (destruction) (reviewed in [22, 31]).

Numerous filamin isoforms exist in metazoan cells (reviewed in [22, 31]) and in some cases their cellular distribution suggests that certain isoforms may have specialized roles within the cell [35]. In muscle cells, filamin is locally concentrated at specific points called Z-lines, but in non-muscle cells filamin generally remains distributed throughout larger actin-based structures such as the lamellipodium, cortical actin, stress fibers and at sites of adhesion [reviewed in (4)].

Filamin not only binds to membrane receptors and to the Rho family of GTPases to influence actin organization (reviewed in [31]), but can itself directly transduce mechanical signals (e.g. stress) to regulate the cell stiffness [36] and possibly alter cellular adhesion [37]. Filamin can be phosphorylated by numerous kinases including cAMP-dependent protein kinase (i.e. protein kinase A) [38, 39] and protein kinase C [40]. Filamin phosphorylation not only regulates its interaction with other proteins and affects its ability to cross-link actin, but also regulates its stability and proteolysis (destruction) (reviewed in [22, 31]).

Fimbrin[Edit]

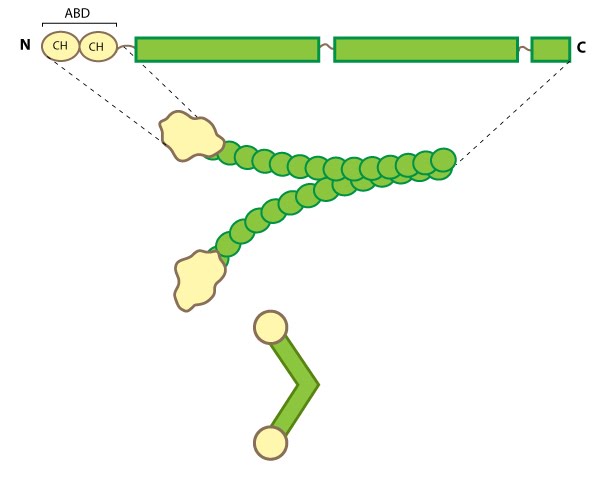

Fimbrin (aka plastin homologue, accumentin) is an actin binding protein that was originally identified in microvilli [41, 42].  Figure 4. Fimbrin: This

schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of fimbrin and

highlights the relevant domains for binding to actin filaments.Fimbrin represents one of the most basic structures of an actin crosslinking protein; it contains a calcium-binding domain consisting of a pair of EF hand domains, and a pair of actin binding domains (ABDs) composed of two calponin homology (CH) domains (see figure below). However no calcium sensitivity has been demonstrated for the EF domains. Fimbrin is found in a number of organisms from yeast to humans and those organisms containing multiple isoforms (e.g. humans have three) frequently exhibit isoform expression that is cell type or tissue specific (reviewed in [43, 44]).

Figure 4. Fimbrin: This

schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of fimbrin and

highlights the relevant domains for binding to actin filaments.Fimbrin represents one of the most basic structures of an actin crosslinking protein; it contains a calcium-binding domain consisting of a pair of EF hand domains, and a pair of actin binding domains (ABDs) composed of two calponin homology (CH) domains (see figure below). However no calcium sensitivity has been demonstrated for the EF domains. Fimbrin is found in a number of organisms from yeast to humans and those organisms containing multiple isoforms (e.g. humans have three) frequently exhibit isoform expression that is cell type or tissue specific (reviewed in [43, 44]).

Figure 4. Fimbrin: This

schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of fimbrin and

highlights the relevant domains for binding to actin filaments.

Figure 4. Fimbrin: This

schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of fimbrin and

highlights the relevant domains for binding to actin filaments.Localization and function

Fimbrin primarily modulates the cytoskeleton organization of microvilli and stress fibers. Although fimbrin has been at the ends of stress fibers [45, 46][18]. Fimbrin is not only dispersed throughout the lamellipodium and lamella, but it is also found in various larger actin-based structures such as stereocilia [47][48, 49], cell adhesion sites, microspikes and membrane ruffles [42, 7][48] and it’s small size allows it to crosslink actin into rigid bundles.

α-actinin[Edit]

α-actinin is an actin-binding protein [50] and component of the actin crosslinking functional modules; it lacks G-actin binding activity and lacks actin initiation/nucleation activity [51]. α-actinin is an important organizer of the cytoskeleton that belongs to the spectrin superfamily (which includes spectrin, dystrophin, and related homologues). α-actinin is present in a number of diverse organisms including protists, invertebrates, and birds; mammals have at least four α-actinin genes that together account for 6 different α-actinin proteins whose expression profile is tissue specific (reviewed in [52]).

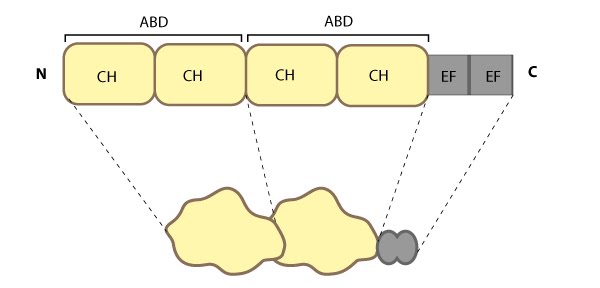

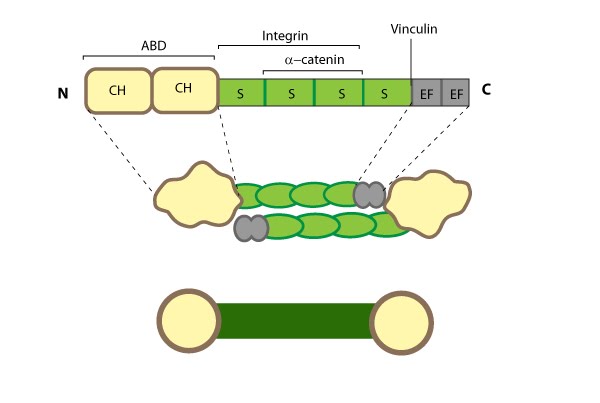

All α-actinin proteins have a flexible amino-terminal F-actin binding domain (ABD, composed from two calponin homology [CH] domains), a central rod containing spectrin repeats (S or SR), and a carboxy-terminal calmodulin (CaM)-like domain composed of EF-hand calcium-binding motifs (see figure below). Calcium inhibits the association of non-muscle α-actinin isoforms with F-actin [53, 54, 55] whereas binding of the muscle isoforms is insensitive to calcium [56].

Figure 5. Alpha (α)-actinin: This schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of α-actinin (reviewed in [52]) and provides examples for how α-actinin is represented in figures throughout this resource. Relevant domains/regions that are believed to be important for actin binding and protein-protein interactions are highlighted (actin binding domain (ABD) [57], β-integrin [58, 59], α-catenin [60] and vinculin [61, 62]).

Figure 5. Alpha (α)-actinin: This schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of α-actinin (reviewed in [52]) and provides examples for how α-actinin is represented in figures throughout this resource. Relevant domains/regions that are believed to be important for actin binding and protein-protein interactions are highlighted (actin binding domain (ABD) [57], β-integrin [58, 59], α-catenin [60] and vinculin [61, 62]).

The basic organization of the ABDs is quite similar in other members of the α-actinin superfamily such as filamin, fimbrin, and parvin [63]. α-actinin binds F-actin [57] and other molecules such as phophatidylinositol-bisphosphate (PIP2) [64], cell adhesion proteins (e.g. integrins [58, 59]) and signaling enzymes (e.g. PI3K [65]). It also interacts with vinculin through the 4th S repeat [62] and this interaction acts as a regulatory switch in adherens junctions [61]. Intramolecular contacts that sterically prevent α-actinin from interacting with actin filaments and integrins are relieved by PIP2 binding to the ABD [66] and this regulates α-actinin dynamics [67].

Dimerization of α-actinin via the rod domain is also essential for crosslinking actin [68] and for binding to other proteins (e.g. zyxin) [69], therefore, a dimer has functional domains at both ends [70]; this organization allows them to bind to adjacent actin filaments [71]. The smaller size of the α-actinin dimer combined with flexible hinges at the ABDs, makes α-actinin a versatile actin crosslinker capable of forming variable orientations and angles between actin filaments, as well as forming tighter bridges between filaments (such as those found in actin bundles) (reviewed in [52]).

Figure 5. Alpha (α)-actinin: This schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of α-actinin (reviewed in [52]) and provides examples for how α-actinin is represented in figures throughout this resource. Relevant domains/regions that are believed to be important for actin binding and protein-protein interactions are highlighted (actin binding domain (ABD) [57], β-integrin [58, 59], α-catenin [60] and vinculin [61, 62]).

Figure 5. Alpha (α)-actinin: This schematic diagram illustrates the molecular organization of α-actinin (reviewed in [52]) and provides examples for how α-actinin is represented in figures throughout this resource. Relevant domains/regions that are believed to be important for actin binding and protein-protein interactions are highlighted (actin binding domain (ABD) [57], β-integrin [58, 59], α-catenin [60] and vinculin [61, 62]).The basic organization of the ABDs is quite similar in other members of the α-actinin superfamily such as filamin, fimbrin, and parvin [63]. α-actinin binds F-actin [57] and other molecules such as phophatidylinositol-bisphosphate (PIP2) [64], cell adhesion proteins (e.g. integrins [58, 59]) and signaling enzymes (e.g. PI3K [65]). It also interacts with vinculin through the 4th S repeat [62] and this interaction acts as a regulatory switch in adherens junctions [61]. Intramolecular contacts that sterically prevent α-actinin from interacting with actin filaments and integrins are relieved by PIP2 binding to the ABD [66] and this regulates α-actinin dynamics [67].

Dimerization of α-actinin via the rod domain is also essential for crosslinking actin [68] and for binding to other proteins (e.g. zyxin) [69], therefore, a dimer has functional domains at both ends [70]; this organization allows them to bind to adjacent actin filaments [71]. The smaller size of the α-actinin dimer combined with flexible hinges at the ABDs, makes α-actinin a versatile actin crosslinker capable of forming variable orientations and angles between actin filaments, as well as forming tighter bridges between filaments (such as those found in actin bundles) (reviewed in [52]).

α-actinin localization and function

α-actinin primarily influences the cohesiveness and mechanics of the cytoskeleton by cross-linking actin filaments and other cytoskeleton components to create a scaffold that imparts stability and forms a bridge between the cytoskeleton and signaling pathways. α-actinin interacts with numerous (~30) components in the cell (reviewed in [72]) and certain α-actinin isoforms (and related proteins) appear to be active in the nucleus (reviewed in [73]). α-actinin is mainly found at the leading edge of migrating cells and it is an important component of adhesion modules [74]. Dendritic spines are also rich in α-actinin and it appears to play a role in neuritic outgrowth [75]. Lastly, α-actinin is believed to be the primary crosslinking protein in stress fibers [76] and it plays a major role in the maturation of focal adhesions [77]. Localization of α-actinin to the plasma membrane is controlled by a number of interactions with membrane lipids and transmembrane receptors (reviewed in [51]). For example, binding of PIP2 at the plasma membrane causes a conformational change in the CaM-like domain that subsequently increases α-actinin’s affinity for actin and its ability to interact with other cytoskeletal components (e.g. titin [78]) (reviewed in [52]).

I-BAR and Other Proteins/Factors[Edit]

Proteins containing I-BAR (inverted Bin/amphiphysin/Rvs i.e. IRSp53 Missing-in-metastasis homology Domain or IMD) cooperate with various components of actin filament assembly, to promote filopodia protrusion, via several mechanisms including the stimulation of F-actin crosslinking [79].

A specific example of an I-BAR domain-containing actin crosslinker and scaffolding protein is IRSp53, which localizes to the tips of filopodia [80]. The activity of IRSp53 is enhanced by Cdc42 or Rac1 GTPases during filopodia formation [81, 82, 83]. Although this protein performs several functions and binds other actin regulators such as Mena (a Ena/VASP family protein [82]) and formin (e.g. mDia1 [84]), its role in F-actin binding and crosslinking is well established and has been attributed to its IMD domain [83, 85].

Additional molecules contribute to the cross linking of actin filaments and these include fimbrin as well as lesser known actin crosslinking proteins such as Arg (Abl-related gene). This latter example is involved in lamellipodial protrusion, independent of its kinase activity, but concomitant with its microtubule binding activity [86].

A specific example of an I-BAR domain-containing actin crosslinker and scaffolding protein is IRSp53, which localizes to the tips of filopodia [80]. The activity of IRSp53 is enhanced by Cdc42 or Rac1 GTPases during filopodia formation [81, 82, 83]. Although this protein performs several functions and binds other actin regulators such as Mena (a Ena/VASP family protein [82]) and formin (e.g. mDia1 [84]), its role in F-actin binding and crosslinking is well established and has been attributed to its IMD domain [83, 85].

Additional molecules contribute to the cross linking of actin filaments and these include fimbrin as well as lesser known actin crosslinking proteins such as Arg (Abl-related gene). This latter example is involved in lamellipodial protrusion, independent of its kinase activity, but concomitant with its microtubule binding activity [86].